Velázquez in Rome

When Diego Velázquez arrived in Rome in 1649 on a buying trip for the King of Spain, he set his portraitist’s eye on the highest ranking sitter in the world: the Pope. Innocent X Pamphilj, though not so emphatically a patron of the arts as his predecessor, Urban VIII Barberini (to whom we owe Bernini’s decorative scheme for the interior of St. Peter’s, including the Baldacchino for which the Barberini pope may or may not have melted the bronze from the dome of the Pantheon), was in the midst of embellishing Rome for the Jubilee Year 1650. The story goes that when Velázquez offered to paint Innocent’s portrait, the pontiff asked the artist to first complete a test portrait. Thus it is to Innocent X that we owe the portrait of Juan de Pareja, Velázquez’s slave, who stood beside his likeness upon its exhibition at the Pantheon on the Feast of St. Joseph, 1650. The acclaim was universal and Velázquez won the commission to paint the Pope. Today Velázquez’s Portrait of Innocent X hangs next to Bernini’s portrait bust of the same pontiff, also commissioned for the 1650 Jubilee, in the Galleria Doria-Pamphilj on the Via del Corso. For centuries the portrait has been studied and copied by portraitists as the supreme masterpiece of their art.

The Rome Prize

In 2020-2021, sacred artist and ecclesiastical portraitist Gwyneth Thompson-Briggs hopes to follow Velázquez to Rome, retracing his footsteps and brushstrokes, including those of the Portrait of Innocent X. To this end, Gwyneth has applied for the Rome Prize, a fellowship for artists and scholars at the American Academy in Rome. As a recipient of the Prize, Gwyneth would live at the Academy in Trastevere and spend her days studying and copying Classical, Renaissance, and Baroque masterpieces in and around the Eternal City.

The American Academy’s Rome Prize is modeled on the storied Prix de Rome of the French Academy in Rome. France began funding Roman fellowships for her most promising painters and sculptors in 1663 under the reign of Louis XIV. Beneficiaries—including Hyacinthe Rigaud, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Jacques-Louis David, and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres—stayed at the French Academy in Rome founded by Louis XIV’s minister of finance, Jean-Baptiste Colbert. Later known as the Prix de Rome and extended to architects, composers, and engravers, the idea was to amplify French greatness through direct contact with the greatness of ancient and papal Rome.

In 1896, similar fellowships began to be established through the newly formed American Academy in Rome. Like its French model, the American Academy aimed to cultivate American talent by bringing emerging artists into the fount of Western culture. Early Fellows of the American Academy like John Russell Pope, architect of the National Gallery of Art and the Jefferson Memorial in Washington, and Paul Chalfin, designer of the Villa Vizcaya, clearly situated themselves within the Roman tradition.

For Gwyneth, as for any artist working within the Western tradition, Rome is a constant influence. “I first became aware of how important studying in Rome is for artists when I was a girl, while reading a life of Anthony van Dyke,” she recalls. Though Van Dyke was enjoying success in his native Flanders, he elected to spend several years in Italy—in Rome, Venice, Palermo, and especially Genoa—perfecting his craft. Gwyneth recalls, “The author reflected on how extraordinary it must have been for a painter from the grey North to come to Rome and encounter the rich patrimony of the South, and how it affected his work. As a girl living outside of Tacoma, I understood immediately.” Later she read about the French Academy and how pivotal the Prix de Rome was for many great artists of the 18th and 19th centuries. “The more I study,” Gwyneth says, “the more I realize how important studying from the heart of the tradition is.”

Encouraged by a former colleague, and recognizing that the time was right, Gwyneth decided to apply for the Rome Prize this Fall. “It was only in January 2019 that my husband and I began to dedicate ourselves full-time to sacred art and raising our young children. Going to Rome now would have a transformative effect not just on my art, but on each member of my family,” says Gwyneth.

Receiving the prize is a long shot, especially because the Academy seems to have excluded traditional artists since the start of the Atomic Age. “‘Man proposes, God disposes,’ goes the saying,” says Gwyneth. “But just because winning the Rome Prize is unlikely, I don’t want to place limits on God. We’re very much trying to be docile to the Holy Ghost. He’ll know whether going to Rome is the right thing for our family at this time,” she says. As far as the Academy’s exclusion of artists working within the tradition rooted in Rome, Gwyneth says, “I feel like I’m offering the Academy an opportunity to return to its roots as an institution that promotes American artistic development in continuity with the roots of our civilization.”

Why Velázquez is Gwyneth’s ideal guide to Rome

Gwyneth elected to propose a project retracing the Roman sojourns of Velázquez in 1629-30 and 1649-51, rather than a Rome-based artist, because she sought a guide who was also an outsider to the masterpieces of Roman art. “Velázquez visited Rome for the first time when he was about thirty. He had already been well formed in Spain and there is obvious continuity between his pre-Roman and post-Roman work. Like him, I would come to Rome having received a formation in my own country, but seeking further development. I want Velázquez to guide me in how not to forget but rather to transform the training I’ve already received in the light of Rome.”

Gwyneth also sees a deep kinship between Velázquez’s style and her own. “Each artist has his own way of running the brush across the canvas; it’s a painter’s handwriting,” she explains. “Velázquez’s handwriting is so compelling to me. It’s almost alchemical, the way these messy, apparently haphazard smears of paint, when viewed from a few steps back, transform into gold—a shimmering surface that perfectly captures the effects of light. I see the faintest echo of his gesture in my own brushwork. I want to give strength to that relationship.”

Part of Velázquez’s greatness is his restraint, says Gwyneth. She sees him as a great foil to the Romantic myth of the Promethean artist. “He was a consummate professional who cultivated relationships with patrons and completed projects on time and within budget. Of course he was also a genius,” says Gwyneth. She perceives his prudential restraint in his paintings: “Both in the palette, focused on black, and in the brushwork, Velázquez holds back everything until the last moment, when he gives a few tiny accents that spark life into the whole. By studying Velázquez and growing in the virtue of prudence, I hope to grow in artistic restraint, too.”

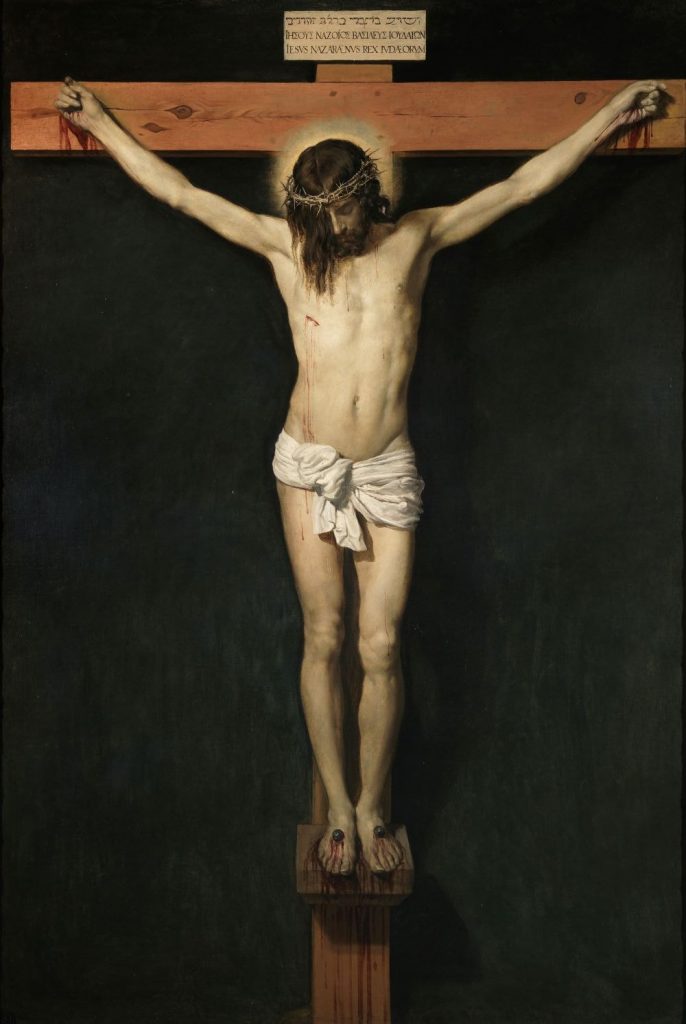

Despite such masterpieces as his Crucifixion and Coronation of the Virgin, Velázquez is primarily known as a portraitist. Gwyneth has a secondary focus in ecclesiastical portraiture, but her primary field is sacred art. To those who might therefore consider Velázquez an odd master, Gwyneth responds that Velázquez’s own master (and father-in-law), Francisco Pacheco, was primarily a sacred artist. More importantly, Gwyneth contends that a Christian worldview animates all Velázquez’s work: “Whether he painted the King, his slave, or a court dwarf, Velázquez always depicts the human dignity of his sitter. Students are always surprised to learn that Juan de Pareja was Velázquez’s slave; they usually assume he was a figure of worldly importance. Alternately, when Innocent X saw his finished portrait, he is reported to have replied, ‘Troppo vero’—’All too true.’” Gwyneth also notes that the Crucifixion, perhaps Velázquez’s greatest sacred work, was created soon after the return from his first stay in Rome; scholars have long speculated on how it was influenced by his Roman sojourn.

During Gwyneth’s stay in Rome, she would make studies of the classical and Renaissance masterpieces Velázquez studied, as well as familiarizing herself with the works of Velázquez’s contemporaries in Counter-Reformation Italy. On his first tour, Velázquez befriended fellow Spaniard Jusepe Ribera, based in Spanish Naples; on his second tour, Velázquez returned to Naples to revisit his old friend. Especially during the second tour, Velázquez was active in the cultivated artistic circle in Rome that included Nicolas Poussin and Bernini. “It would be especially interesting to compare Bernini and Velázquez’s approach to Innocent X,” says Gwyneth.

Gwyneth and her Roman contemporaries

Though modern Rome may not provide a milieu so cultivated as the Rome of Velázquez’s day, Gwyneth would nonetheless prize the company of her peers and contemporaries. “I’ve recently made contact with another sacred artist and mother—Margherita Gallucci—whose work I admire. I would love to get to know her in person, as well as Giovanni Gasparro, another contemporary Italian sacred artist whose work I very much admire,” says Gwyneth. And how would Gwyneth fit in with the Rome Prize cohort? She would particularly value exchanges with scholars of early modern Rome, who might be able to help her better understand the Rome Velázquez knew, and for whom she might provide a living link to Rome’s artistic tradition.

Gwyneth also sees common ground even with artists working against or in ignorance of eternal Rome. “Anyone who applies for the Rome Prize must believe there’s something that Rome can possibly give us, however inchoate or confused our ideas may be about what that something is,” she says. Gwyneth considers herself blessed to have been exposed to ideas and cultural objects that allowed her to discern authentic art from various modern imposters, and thus to seek out quality technical training. “When I see people mired in the confusion of the contemporary art world, I think, ‘that was me in the past, and there but for the grace of God go I.’ Even today, I don’t think most people are drawn to art because they want to play a political game of wit; I think most people are drawn to art because they have a genuine, if unnamed love for real beauty and real transcendence, but then fall prey to the lies of the contemporary culture in general and the contemporary art world in particular. Rome is just one possible means through which God can transform someone professionally and spiritually. Only God knows where an artist or a soul will be tomorrow. As for me, compared to Velázquez or Ribera or Caravaggio, I have no technical ability either. We all stand in need of the artistic and spiritual treasures of Rome.”

Read an extended version of Gwyneth’s Rome Prize project proposal.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks