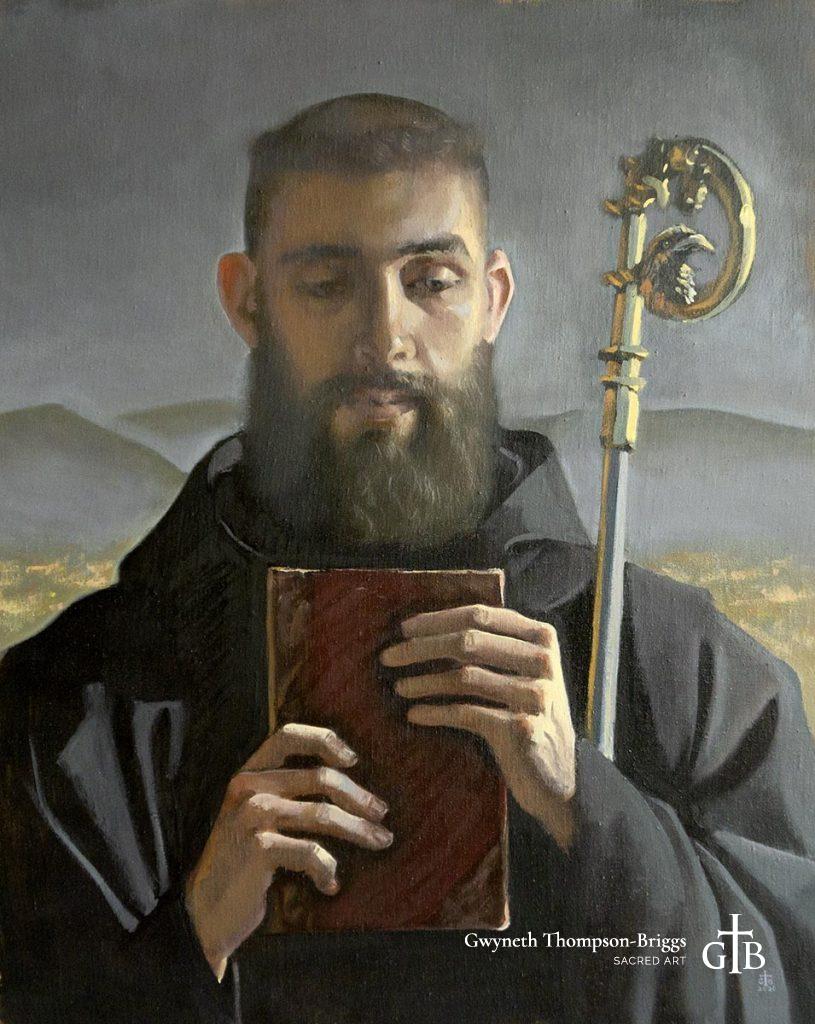

A quiet Umbrian glow suffuses the new portraits of Saints Benedict and Scholastica by sacred artist Gwyneth Thompson-Briggs. She achieved it by painting mostly on sunny August afternoons, when the light in her studio reflected off the oak floors, casting a soft gold hue on her models’ features and costumes. The golden light at once roots the saints in their Italian homeland and suggests their heavenly glory. Designed to be fitted into seventeenth century frames as altarpieces for side chapels in a monastic church, the paintings are meant to complement the whispers of private Masses and prayer.

To show the vitality of the Benedictine charism, Gwyneth depicted the saints at about thirty-three, the age of Christ at the consummation of His life on earth. Reading St. Gregory the Great’s Life of Benedict in preparation for the project introduced her to the vigor of Benedict, “renouncing the world in the prime of his life for a life of manful asceticism, laying down monastic rules that have endured to our day,” she says. “I wanted to impart that vigor to the portrait.” The client agreed, suggesting Charlton Heston in The Ten Commandments as a visual reference point. For St. Scholastica, Gwyneth was asked to depict a cross between Grace Kelly, Sophia Loren, and Julia Child. “I knew someone who was just the type,” Gwyneth recalls, “and she had a brother with the ascetic gravitas of Heston.” She was looking to work in part from sibling models, since Benedict and Scholastica were siblings and probably twins.

For the habits, Gwyneth borrowed from various Benedictine houses. “I’m so grateful to the Benedictine nuns and monks who loaned habits for this project,” says Gwyneth. “They were extraordinarily gracious, as was my pastor, who leant a crosier. Since it is the habits that establish the saints as Benedictines, I was striving for the greatest possible authenticity.”

She was especially delighted with the many-creased wimple, which came from the Benedictine Sisters of St. Emma’s Monastery in Pennsylvania[link]. “The folded wimple provided a sober geometric frame to offset the features of the face, much like the gold setting of a precious stone.” Gwyneth found herself meditating on how a veil and wimple emphasize the face, and hence the person. “Scholastica demonstrates the way a nun’s habit brings her heart into focus,” Gwyneth says.

Revealing the heart was part of why Gwyneth chose to depict St. Scholastica gazing outward at the viewer. “We know much less about Scholastica than we do about Benedict,” Gwyneth explains, “so I wanted to supply a visual intimacy that could foster devotion to her.”

The outward gaze also seemed consistent with the written portrait of Scholastica in St. Gregory the Great’s Life. Gregory recounts that Scholastica begged her brother to prolong his last visit to her before she died (a death he does not seem to foresee). Benedict protested that (in fidelity to his rule) he had to return to his monastery, but Scholastica prayed to God and immediately a thunderstorm erupted, forcing him to spend the night “in holy conversation about the spiritual life” (Life XXIII.4, trans. Carolinne White, in Early Christian Lives, London: Penguin, 1998, p. 199). Gregory writes that “it was by a very just judgement that her power was greater [than Benedict’s] because her love was stronger” and “God is love” (Life XXIII.5, p. 200; 1 John 4:16). After spending the next three days at prayer in his cell, Benedict saw his sister’s soul “penetrat[ing] the mysterious regions of heaven in the form of a dove” (Life XXIV.1, p. 200).

“In Gregory’s story I glimpsed Scholastica’s warmth,” says Gwyneth, “a warmth like that I’ve experienced in the hospitality of Benedictine sisters today, and that attests to a great charity. The Rule is at the service of love, for the Lord is love.”

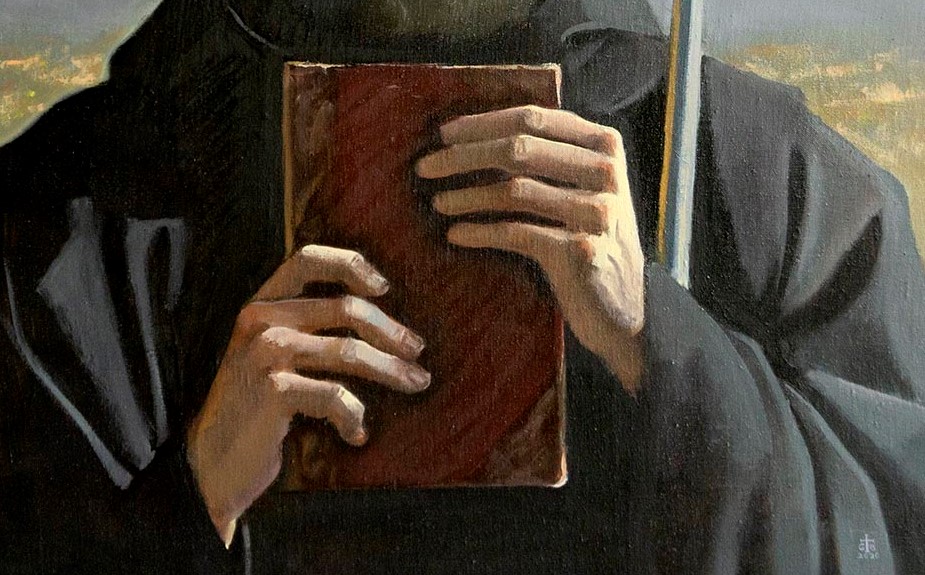

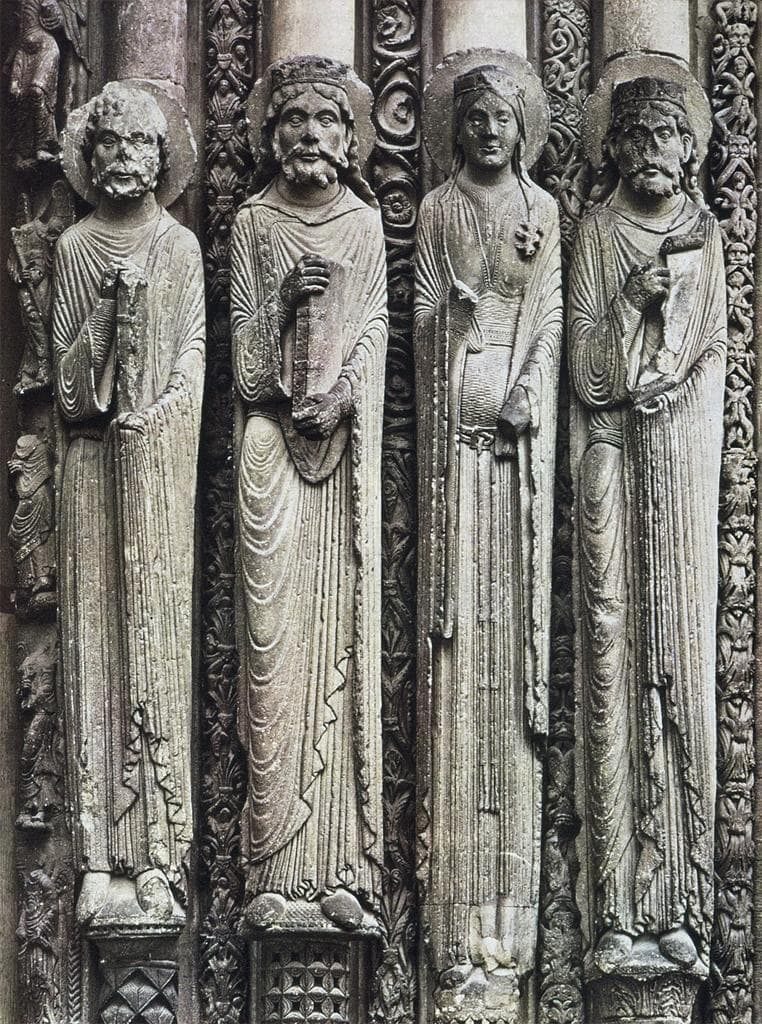

In contrast to his sister, Benedict looks downward toward his Rule in Gwyneth’s portrait. “I wanted to show the marvelous stability bequeathed to the Benedictines and the world by his Rule. The flower of the Rule is charity—typified in St. Scholastica—but the root of Benedictine charity is the Rule.” To manifest this stability, Gwyneth recalled the Gothic jamb statues of Chartres in her depiction of Benedict’s hands holding his Rule. “There’s a solidity and simplicity to this part of the picture especially, but also in the symmetrical composition of both portraits, which hearkens back to Gothic and even Romanesque architecture. In a Baroque painting, everything would have been composed along diagonals,” she explains.

The handling of the paint, however, is decidedly Baroque, in the tradition of Rubens, Velazquez, and Tiepolo. The brushwork is fairly loose, especially in the crosiers. “Loose strokes are especially effective at representing metal,” says Gwyneth. The gilt crosiers, which are used by abbots and abbesses as well as bishops and form part of the traditional iconographies of Benedict and Scholastica, recall the celestial glory that saints anticipate during their lives and help communicate to us through their memory and intercession. “The sparkling crosiers function almost like haloes,” Gwyneth suggests.

In addition to placing the crosiers in opposite hands, Gwyneth sought other ways to dynamically unify the paintings. “I wanted the composition of the two paintings to complement but not repeat one another. They are twins, not a matching pair.” One of the solutions Gwyneth found was highlighting the landscape behind Benedict and the stormy night sky above Scholastica. The device also fits Gregory’s anecdote about the siblings. Benedict and his Rule rise like a palm from the soil; Scholastica hovers like a dove, inviting us to mystical conversation with Love.