“Poca vita mortal m’era rimasa,

quando fui chiesto e tratto a quel cappelo,

che pur di male in peggio si travasa.”

– Dante, Paradiso, canto 21, vv. 124-26

“Little of mortal life remained to me,

When I was called and dragged forth to the hat

Which shifteth evermore from bad to worse.”

– Dante, Paradiso, canto 21, vv. 124-26, trans. Longfellow

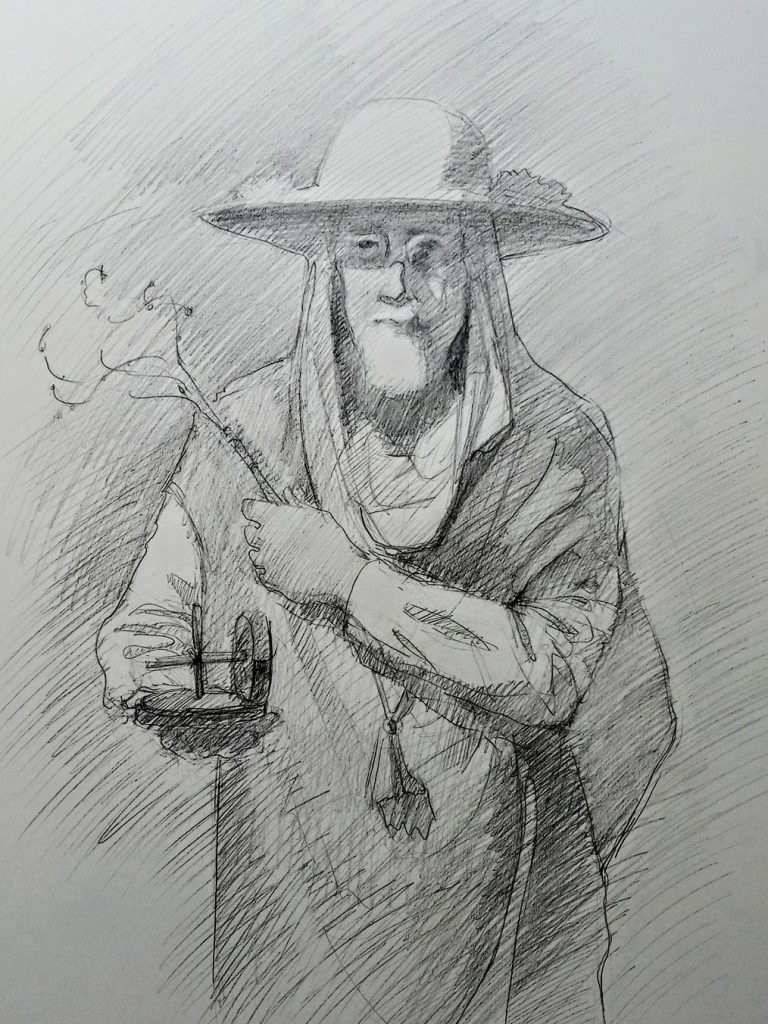

Thus from glory—in Dante’s telling—does St. Peter Damian recount his reception of the galero cardinalizio, the cardinal’s hat and symbol of office. Alas for Damian, Gwyneth Thompson-Briggs has called and dragged him forth again—this time from Paradise to her St. Louis studio—to don the scarlet for a new portrait. As soon as she received an inquiry about a commission to paint St. Peter Damian, she knew that she wanted to paint him as a cardinal, for reasons artistic and theological:

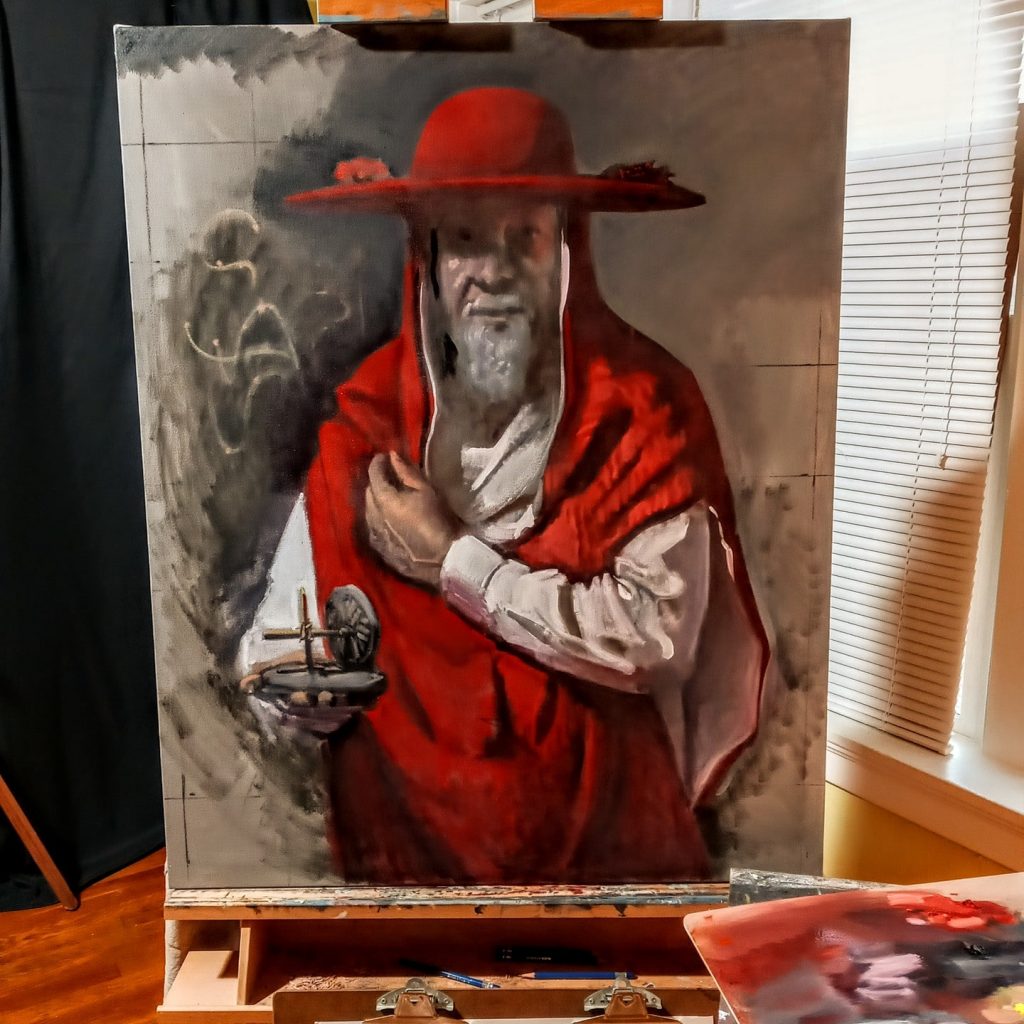

As a painter, I longed to try my hand again at painting red moiré silk. I also wanted to exploit the contrast between the organic effects of the silk and the geometric idealism of the hemispherical galero. As a sacred artist, I considered that this painting needed to convey the awesome paternal authority of the holy prelate. Much of what St. Peter Damian fought to uproot from the Church in the eleventh century has taken root again, and as in Damian’s day, true reform will only be accomplished through the application of that authority. The galero, robes, and pontifical gloves are meant to communicate the authority with which Christ has vested His Bride.

The patron—the St. Peter Damian Society—heartily agreed. Founded by laymen to promote a truly Catholic response to the clerical abuse crisis, the Society advocates the clear denunciation of sin and the wholehearted embrace of penance on the part of the hierarchy. “For too long,” says the Society, “the language of bureaucrats and businessmen has been allowed to supplant that of the saints—of sackcloth and ashes, of bell, book, and candle.”

St. Peter Damian himself (1007-1072) led a life of mortification and contemplation as an eremitical monk in central Italy. After becoming prior of his community he began raising his voice to denounce widespread sexual perversion and simony among the clergy. He was unafraid to rebuke bishops and popes for failing to extirpate vice, and eager to lend them his help in implementing dangerous reforms. His efforts eventually bore fruit through the cooperation of reforming popes like Leo IX; Stephen X, who created Damian cardinal; and Alexander II. Damian also worked closely with Hildebrand, the future Pope St. Gregory VII. Widely venerated since his death, in 1823 Leo XII added St. Peter Damian’s feast to the universal calendar and proclaimed him Doctor of the Church.

In the preface to his frank and influential Book of Gomorrah, Damian compares himself to a doctor combatting plague: “It is shameful to relate such a disgusting scandal to sacred ears! But if the doctor fears the virus of the plague, who will apply the cauterization? If he is nauseated by those whom he is to cure, who will lead sick souls back to health?” In her portrait, Gwyneth sought to capture the saint’s fearless, clearsighted attention to the moral plague of sin.

The Way of Life and the Way of Death

St. Peter Damian is depicted as a venerable yet virile authority with a white beard and piercing eyes. He faces forward and stares directly out at the viewer, calling him to personal repentance and to the performance of the duty of his state in life in promoting reform in the Church. His eyes, bearing, and finery call us to attention. The ecclesiastical garments remind us that Damian teaches not with his own authority, but with that vested in the Church by Christ Himself.

Lit from the heavens, Damian’s wide-brimmed galero casts a band of shadow over his eyes, alluding to depictions of Lady Justice blindfolded and holding scales. Like Justice, St. Peter Damian applied God’s law to meek and mighty alike. Extending the allusion to Lady Justice, and visually punning on the etymology of “cardinal”—from the Latin cardo, cardinis: a hinge or pivot—Damian holds two opposing objects: a millstone and a disciplina.

The millstone alludes to Our Lord’s warning about those who scandalize the innocent: “But he that shall scandalize one of these little ones that believe in me, it were better for him that a millstone should be hanged about his neck, and that he should be drowned in the depth of the sea” (Matthew 18:6; see also Mark 9:41 and Luke 17:2). For this reason it serves as the symbol of the Society of St. Peter Damian. (See note.)

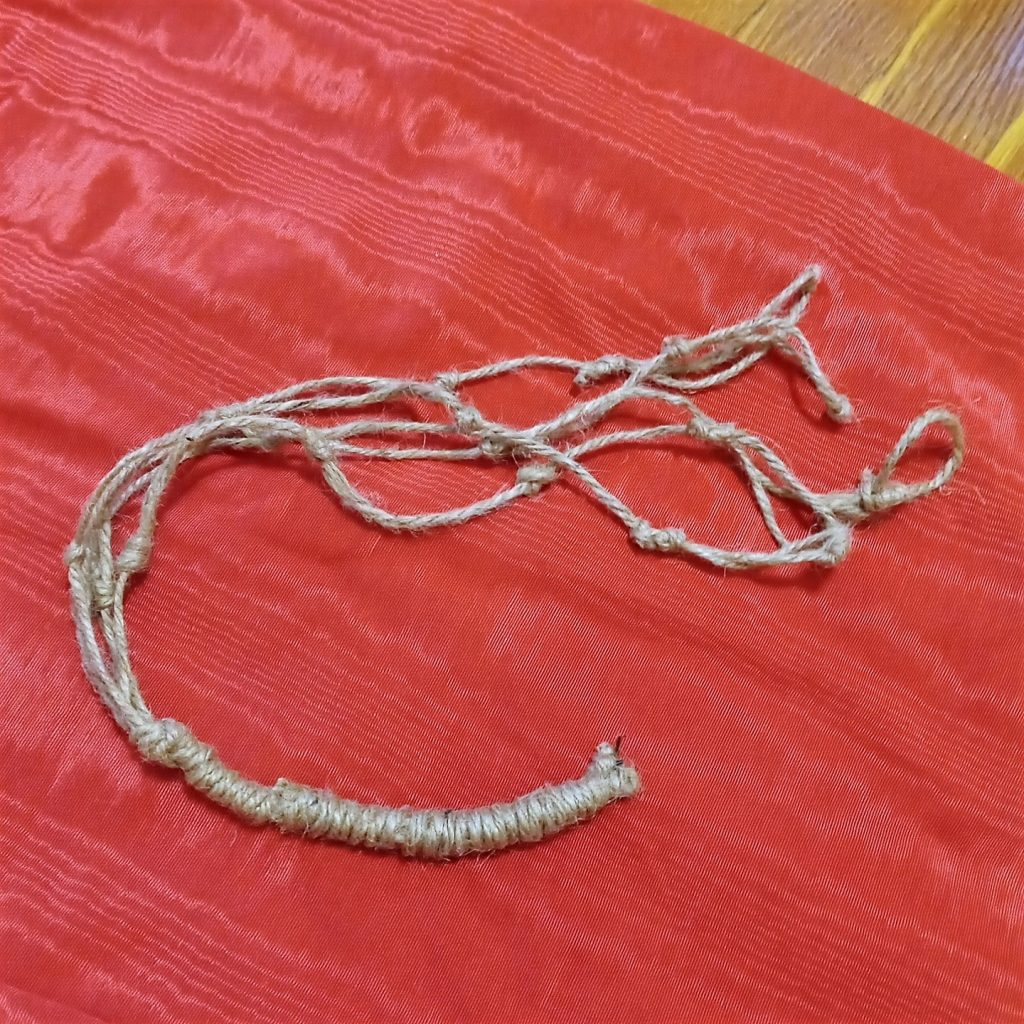

In his other hand the saint holds a disciplina, a knotted cord used to inflict corporal mortification in imitation of Christ’s scourging. St. Peter Damian himself popularized the use of the disciplina among his and other monks. The name derives from the virtue of discipline of which the Wisdom Books speak: “The very first step towards wisdom is the desire for discipline” (Wisdom 6:18, Knox trans.; see also Ecclesiasticus/Sirach 1:34; Psalm 17:36). As the penitential tradition teaches, the humbling of the flesh is a necessary pre-condition for self-mastery and a lifelong remedy for pride. The disciplina is also an implement of divine mercy, whereby God grants those He has already forgiven the means to unite their own meager mortifications to the unspeakable agony of His Son’s saving Passion.

The disciplina and the millstone thus represent the choice between “the way of life” and “the way of death” (Deuteronomy 30:20; Psalm 1) which St. Peter, in conformity with Revelation, recalls to the viewer’s attention. St. Peter raises the discplina, putting it into use, thereby urging the viewer to join him in choosing life.

A Painter’s Painting

Gwyneth conceived the painting in the tradition of Renaissance depictions of St. Jerome as a cardinal. “I didn’t want to get lost in trying to discover what a cardinal might have worn in the 11th century,” she says, “and I wanted him to be instantly recognizable as a cardinal, so I turned to the iconography of St. Jerome,” who lived before the formation of the cardinalate, but served as an advisor to Pope Damasus I and is almost always depicted as a cardinal.

In addition to St. Jerome, Gwyneth looked to Innocent X—in the famous portrait by Velázquez—for visual inspiration. Velázquez is the dominant inspiration behind Gwyneth’s brushwork. “So much of the beauty of Velázquez’s brushwork lies in its confidence,” she says, “a confidence perfectly attuned to convey the confidence of a subject like Innocent X. It seemed advisable to borrow some of that same painterly bravura in depicting St. Peter Damian.”

The bravura brushwork shows up especially in the watered silk. “When light hits the moiré pattern, it creates high contrast, while elsewhere the pattern nearly disappears. You wind up playing lost and found with the it,” Gwyneth explains. Initially, she applied thin layers of paint. Once the underlying color was in place, she loaded her brush and applied thick dabs of paint. “Impasto requires a decisive yet light touch—perhaps like that of a surgeon,” she says.

She painted “wet-on-wet”, applying several layers of paint in a single session. Once she felt confident about her plans for a stretch of the silk, she would block in a large area with alizarin crimson and then paint in more opaque reds: peony, vermilion, and cadmium scarlet. “Painting wet-on-wet gives the brushwork greater fluidity. The paintbrush glides across the surface like a freshly polished skate on ice,” Gwyneth says. Blending gently with the underlying layers, each stroke acquires great subtlety and dynamic range.

This was the first time Gwyneth has worked with vermilion, an old and expensive red pigment that was used by Velázquez and other Old Masters. “I was frankly a little disappointed with it,” Gwyneth admits. “Certainly for potency, it can’t compete with the cadmiums,” which were only invented in the 19th century and first widely exploited by the Impressionists. “I love the dynamism of the cadmiums in the high range. Vermilion is much more subtle,” she says, and when she used vermilion, she found herself mixing in cadmium scarlet. “That’s anathema in certain artistic circles,” Gwyneth confesses, “where the idea prevails that if you want to paint in the tradition of the Old Masters, you have to limit yourself to their materials and tools. My approach is to incorporate inventions that I think the Old Masters would have embraced had they had access to them. I think Velázquez might well have availed himself of cadmium scarlet in painting a cardinal.”

In emphasizing the cardinalatial scarlet, Gwyneth sought to draw attention to the beauty of the office of the cardinalate, which, as always for a prelate, is so much more important than his person:

In our day, many people have forgotten that it is only when the personalities of prelates disappear beneath the trappings of office that the reflected glory of God can shine through them. Ecclesiastical vestments transfigure the poor sinners who wear them, so that instead of the merely human and mundane, we can see in them the resplendent divinity of the Bridegroom, Who has clothed His Bride “in gilded clothing, surrounded with variety” (Psalm 44:10). I wanted the painting to serve in part to remind viewers of this often overlooked but crucial truth of the importance of prelatial splendor.

Gwyneth hopes that her image fosters prayer to St. Peter Damian in particular for and on the part of cardinals. “Humanly speaking, the solution to the current crisis in the Church lies in the hands of the Pope and the cardinals,” she says. She is certain that St. Peter Damian, who not only bears the name of Peter, but served Peter’s successors in his life and died on the Feast of St. Peter’s Chair (February 22), is eager to assist the Holy Father in wisely selecting cardinals for creation—and in assisting the cardinals themselves in personal holiness; in wisely counselling the Pope; and in electing a holy, orthodox, and capable successor.

Note

Since millstones are used to grind wheat, they also bear a Eucharistic connotation. In an Easter sermon, St. Augustine compares the neophytes to wheat “ground and pounded . . . by the humiliation of fasting and the sacrament of exorcism” and by baptism “moistened with water in order to be shaped into bread” (Sermon 227, trans. Wilfrid Parsons). Similarly, St. Ignatius of Antioch compares his martyrdom to the grinding of wheat: “I am God’s wheat and I am being ground by the teeth of wild beasts to make a pure loaf for Christ” (Letter to the Romans 4.2, trans. Cyril C. Richardson). Both Augustine and Ignatius speak of how corporal mortification incorporates the Christian into Christ’s Mystical Body. In this reading, the millstone itself points to the inescapable role of mortification, whether unto perdition or salvation.