[vc_images_carousel images=”407,408,409,410,406,405,404″ img_size=”full” slides_per_view=”3″ partial_view=”yes”]

A Holy Bishop

In 1508, twenty-seven years before being beheaded for proclaiming the indissolubility of marriage, St. John Fisher delivered a sermon on the 101st Psalm. When he came to the fourteenth verse—Tu exsurgens misereberis Sion, quia tempus miserendi ejus, quia venit tempus—“Thou shalt arise and have mercy on Sion: for it is time to have mercy on it, for the time is come”—he added his voice to the Psalmist’s petition, beseeching God’s mercy for the new Sion amidst the decadence and heresy of the early 16th century:

Lord, according to Thy promise that the Gospel should be preached throughout the whole world, raise up men fit for such work. The Apostles were but soft and yielding clay till they were baked hard by the fire of the Holy Ghost. So, good Lord, do now in like manner again with Thy Church militant; change and make the soft and slippery earth into hard stone; set in Thy Church strong and mighty pillars that may suffer and endure great labours, watching, poverty, thirst, hunger, cold and heat; which also shall not fear the threatening of princes, persecution, neither death but always persuade and think with themselves to suffer with a good will, slanders, shame, and all kinds of torments, for the glory and laud of Thy Holy Name. By this manner, good Lord, the truth of Thy Gospel shall be preached throughout all the world. Therefore, merciful Lord, exercise Thy mercy, show it indeed upon Thy Church.

(T.E. Bridgett, Life of Blessed John Fisher, London: Burns & Oates, 1890, pp. 1-3.)

Fisher was Bishop of Rochester, the poorest see in England, and the only English bishop to resist Henry VIII’s attempt to renounce the headship of Catherine of Aragon for the pretended headship of the Church in England. One hero, twenty-one cowards—such were the English bishops in Fisher’s day, a ratio reminiscent of the College of Bishops on Good Friday. Fisher recognizes both realities in his “Prayer for Bishops,” as it has come to be known: he notes that it is only the fire of the Holy Ghost that turned the “soft and slippery” Apostles into “mighty pillars,” and prays that God might again “exercise [His] mercy . . . upon [His] Church” by firing bishops in His kiln.

The Commission

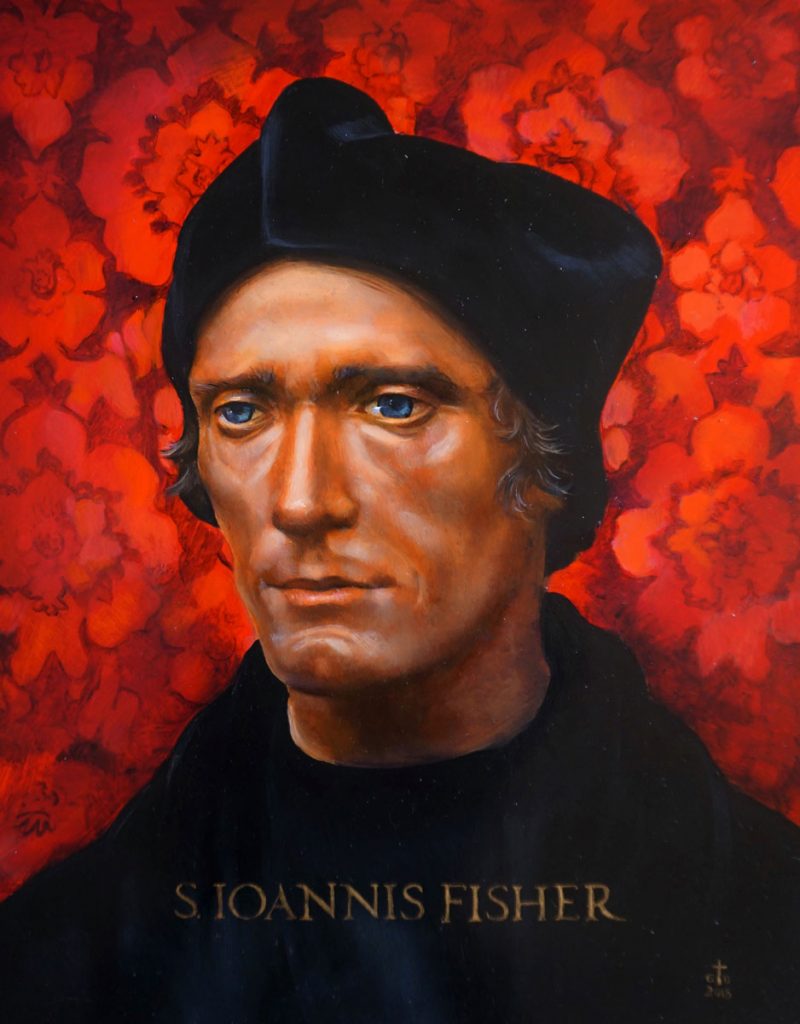

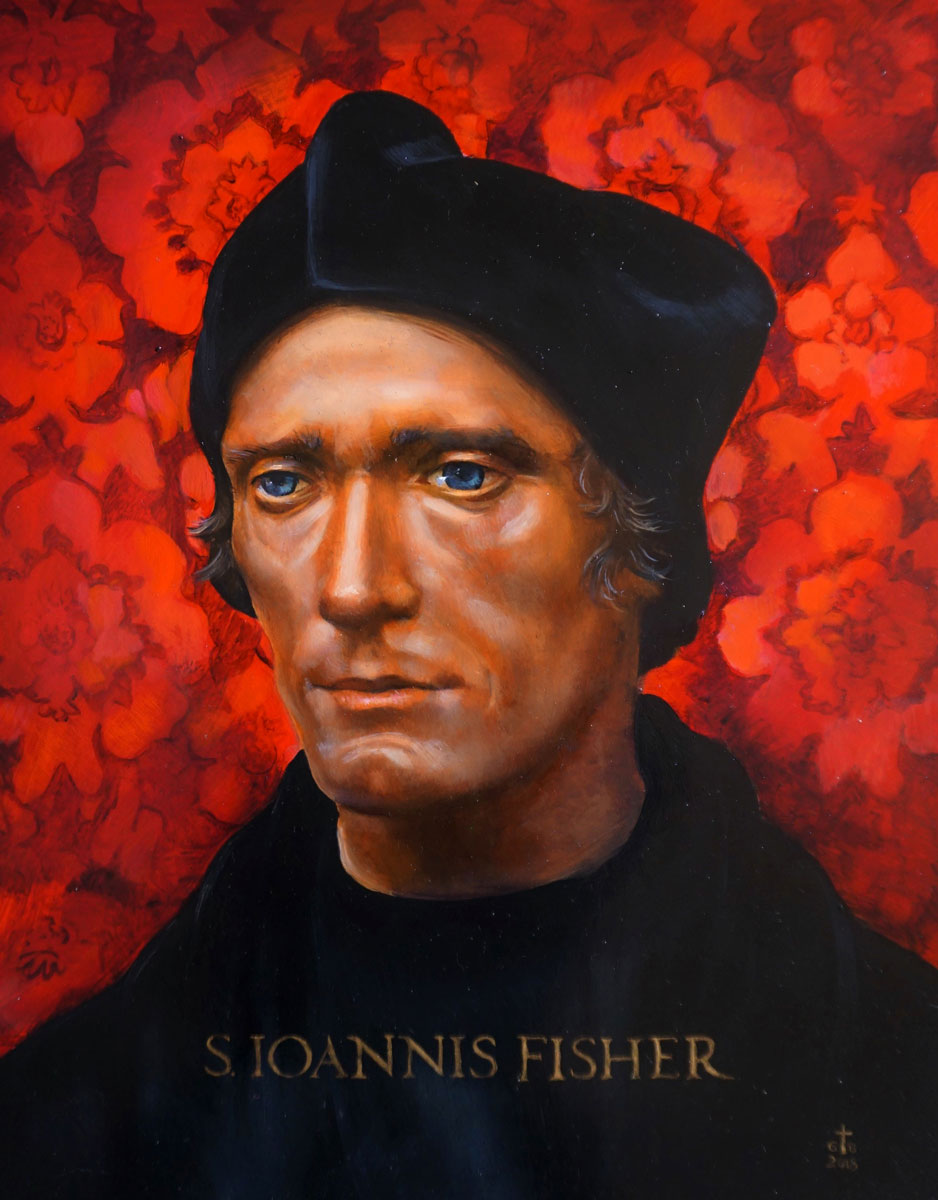

The timeliness of Fisher’s petition for holy bishops, and of Fisher’s own martyrdom for the indissolubility of marriage, was very much in the mind of sacred artist Gwyneth Thompson-Briggs when she received a commission to paint the saint for Our Lady of the Mountains Catholic Church in Jasper, Georgia.

“I was immediately attracted to the project because St. John Fisher is very much a saint for our times. The conditions of his day—political and theological attacks on marriage, a corrupt and craven episcopate—are strikingly similar to our own. As a married woman in the 21st century, I am always looking for ways to give testimony to the beauty of marriage. I also remember visiting Fisher’s grave at St. Peter ad Vincula inside the Tower of London when I was eighteen. When Fr. Byrd reached out to me, I wanted to do Fisher justice.”

Fr. Charles Byrd, Pastor of Our Lady of the Mountains, and two generous parishioners—Kari and Rich Beckman—share a devotion to Fisher and an appreciation of his timeliness: “Bishop Fisher was a man uncompromised, and we live in an age when too many Catholics (from the hierarchy to the laity) compromise too often with the secular ideals,” says Fr. Byrd. Kari Beckman agrees: “John Fisher strikes me particularly in his strength to stand on truth when everyone around him capitulated.”

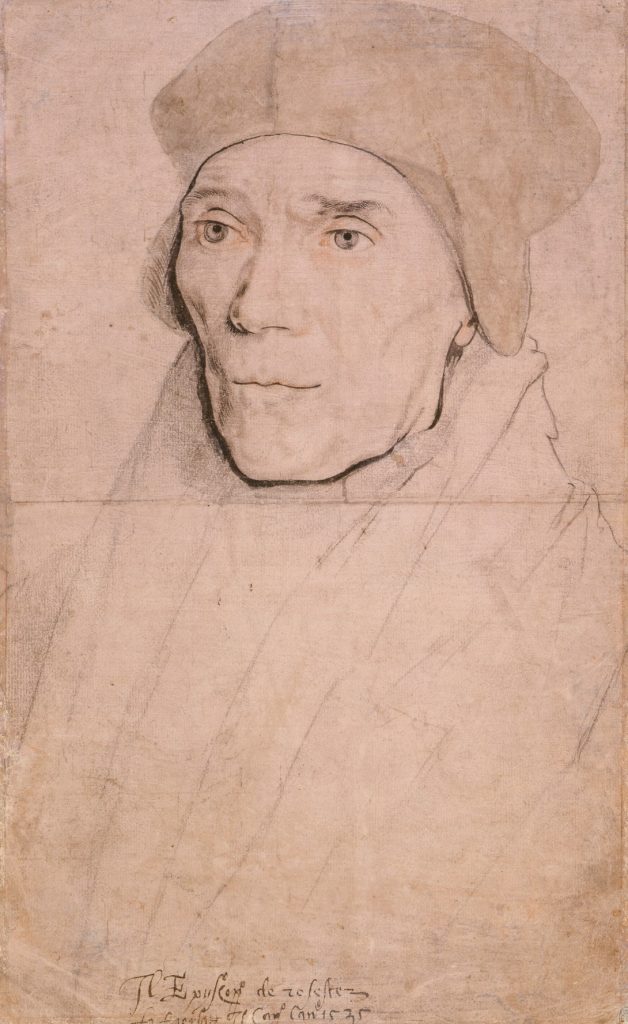

Fr. Byrd and the Beckmans were looking for an artist who could create an original image of Fisher in a style reminiscent of Hans Holbein the Younger, who produced a drawing of the bishop during Fisher’s lifetime.

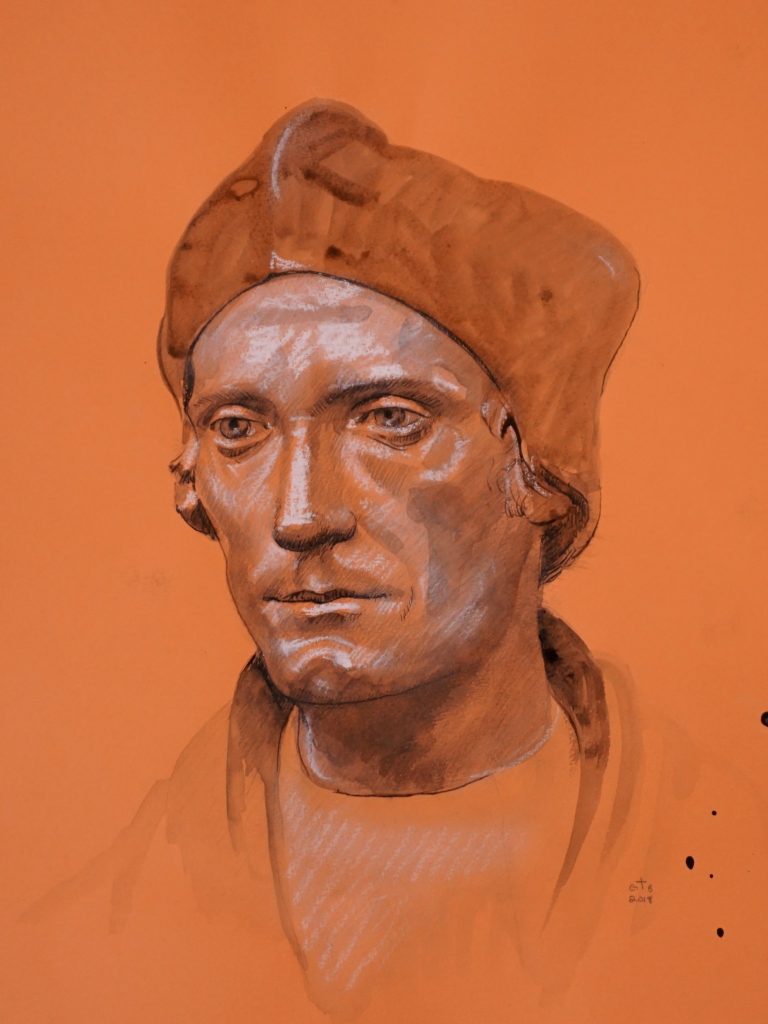

“When Father mentioned Holbein, my first thought was, ‘I’m not up to it,’” Gwyneth remembers. “I’m not Holbein, of course, but also, even though I have a tremendous respect for him, my training and style are very different. Much of my work is inspired by the Spanish baroque tradition, particularly Velázquez. Holbein’s brushwork is much tighter.” Adding to the challenge, Gwyneth was tasked with developing the likeness of Fisher not only from the Holbein drawing, but also from a bust by Florentine sculptor Pietro Torrigiano (1472-1528). She says that her uncertainty about being able to bring off the painting actually inspired her to accept the commission.

Research & Design

Before designing her image, Gwyneth researched Fisher, Torrigiano, and Holbein. In particular, she studied how Holbein’s style developed over the course of his career.

Gwyneth compares combining the Torrigiano bust and the Holbein drawing to stereo vision. “I was seeing two different images, and my job was to combine Torrigiano’s vision with Holbein’s. Torrigiano’s Fisher is much more heroic. The face is elongated, suggesting Fisher’s nobility and fortitude; the carriage of the head on the shoulders conveys the character of a man who saw beyond the mundane. Holbein’s Fisher is less idealized; he’s serious, even grave, but he has funny eyebrows.” But neither artist rendered Fisher photographically, as many realists do today. “They sought to copy the reality of Fisher’s presence rather than merely literal effects of light.”

Gwyneth looked to Holbein especially in placing the figure in a shallow space against a fabric background, in the depth of her blacks—which function as solid pools of color with very little modeling—and in the close attention to the topography of the face with its tiny wrinkles and lines. “Holbein’s figures are very sculptural,” she notes. “Nothing is suggested; everything is fully realized.”

She also departed from Holbein in significant ways, especially in the choice of an intense red damask background. A reference to martyrdom and to the cardinalate, to which Fisher was raised shortly before his death, Gwyneth calls the choice of red “daring.” “Portrait artists like Holbein usually prefer cool tones for backgrounds, in order to contrast with warm flesh tones.” In order to bring the figure into greater relative focus, Gwyneth elected to darken the skin tones and created a hierarchy of brushwork by rendering the damask more loosely than Holbein would have. She patterned the damask from an early 16th century fabric sample that may have been used for divine worship.

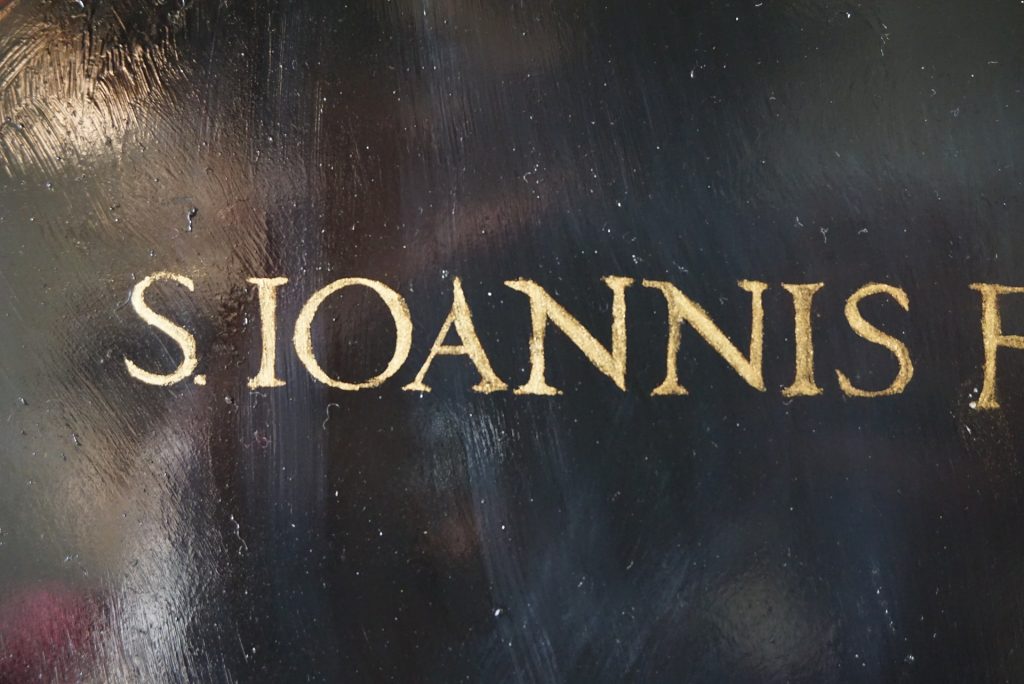

Fr. Byrd asked for the saint’s name to be included in the image, so Gwyneth also researched Renaissance alphabets and decided to use lettering adapted by Giovanni Francesco Cresci from the letters on Trajan’s Column and published in Il perfetto scrittore (Rome, 1570).

Reviving a Tradition

For several years, Gwyneth has been teaching herself Renaissance techniques for oil painting on panel. “Almost no one is teaching Renaissance technique right now, whether in a college or an atelier setting. I’m figuring it out piecemeal from old books and from the paintings themselves. I’d really like to see these techniques revived, because there are possibilities for color and modeling that can’t be attained through the alla prima [or “direct”] approach that prevails in the Academic world. In the direct approach, there is usually only one visible level of paint. Building up transparent layers of oil paints in the way perfected by van Eyck and his followers all over Europe permits greater luminosity.”

She began by drawing four studies of the Torrigiano. “A study is about coming to know the source subject and entering into conversation with it. The eyes in the bust lack pupils, but I needed to supply them for the painting. I kept asking, ‘what would this bust look like if it came alive?’ Very subtle adjustments in the pupils or the irises can change the effect of the gaze dramatically.”

Next she transferred her favorite study onto a gessoed Lindenwood panel by pricking it with small holes and “pouncing,” or tapping charcoal dust through the incisions. This technique keeps the under-drawing from showing through the paint. Gwyneth has previously experimented with sanding and gessoing her own panels. “Preparing the panel requires heating rabbit skin glue to just the right temperature and applying it in many layers, sanding between coats. It’s extremely tedious, and if the temperature or sanding is off, the gesso has a tendency to crack.” This time she opted for an expertly crafted icon board with red oak braces prepared by St. John’s Workshop, a Russian Orthodox supplier. After transferring the study with charcoal, Gwyneth reinforced the drawing with a thin watercolor wash.

The first part of the painting to be completed was the red background. She began by applying a thin layer of cadmium scarlet before imprinting the fabric design with chalk transfer paper and painting the lines with burnt umber. Next she applied a series of glazes with alizeron crimson. “Cadmium scarlet is very high in chroma, and opaque; alizeron crimson is translucent with a pomegranate blush; glazing the scarlet with the crimson provides a richness that neither pigment can supply alone.”

The figure came next, using a standard technique of Renaissance painting: a grayscale underpainting overlaid with thin layers of color. “Adding white to any color makes it opaque. By beginning with a monochrome underpainting, you can focus on modeling value and make the question of hue a separate problem,” Gwyneth explains. After completing the underpainting, she added layers of color over the monochrome flesh. “You really get the sense of a corpse coming alive.” She painted in the hat and cloak once the flesh tones were completed, in order to create clean lines suggestive of real clothing.

Details came next. Certain areas of the background received highlights to give the impression of light catching satin. Gwyneth also payed close attention to precisely rendering the eyes, nose, and mouth.

For the text, she first used chalk transfer paper to carefully space the letters. She covered this with a few thin layers of shell gold. Shell gold—23.75 karat gold suspended in gum Arabic—is used for painting small gold details over oils. “I had seen the shell gold technique on Renaissance works, but I didn’t learn it in art school or the atelier world,” says Gwyneth. “It’s largely fallen out of use in the modern era. Though it can never quite equal the brilliance of gold leaf, shell gold is much easier to apply in thin, delicate designs.” The other major advantage of shell gold is that it can be applied on top of oils, whereas gold leaf has to be applied before oils. “If you were to put gold leaf on top of oils it would seal in the oil and prevent drying. Oils take years to dry completely.”

After letting the painting dry for a couple of weeks, Gwyneth used Gamvar, a synthetic varnish, in lieu of Damvar, which is traditionally made from tree sap. Damvar can only be applied after a year’s drying, and Gamvar can be more easily removed and replaced.

St. John Fisher was completed on November 12, 2018, and blessed and dedicated by Fr. Byrd in the presence of the Beckmans and their fellow parishioners at Our Lady of the Mountains on December 16, Gaudete Sunday.

A Sign of the Resurrection

Gwyneth sees her image as closer in spirit to the Torrigiano bust than to the Holbein drawing. “Although the drawing has a charm and immediacy, I wanted to capture Fisher’s idealism, his heroism, the supernatural reality of him as a man perfected by grace. Torrigiano’s Fisher is probably more handsome than what he looked like in life, but I suspect it is closer to what his resurrected body will look like.” In this way, Gwyneth’s Fisher departs from the naturalism of the Northern Renaissance towards the Italian Renaissance tradition of “adding beauty” to nature. Vasari said that Michelangelo, in his Moses, had prepared the patriarch’s body for the General Resurrection. The anticipation of the life of glory in the midst of our earthly battle is one of the highest purposes of the saints and of sacred art. In the faces of the saints and in their painted effigies, we glimpse the triumph of grace over sin, and win some share in their victories.

Gwyneth cautions that photographic reproductions of sacred art fail to convey the aura of the original works. “There is no substitute for original art. Whether for private or public prayer, authentic art fosters authentic prayer. That’s why I’m so grateful to Fr. Byrd and the Beckmans—and to all patrons of sacred art. Often we don’t know where to place our alms these days, but commissioning traditional sacred art is a way of giving glory to God and promoting the sanctification of our neighbor for, potentially, generations.” St. John Fisher is a work created out of the traditions of past generations of sacred artists for the benefit of future generations of artists and faithful. In it we behold the imperishable glory of a holy bishop faithful unto death to the saving teachings of Christ.

The 101st Psalm that occasioned Fisher’s Prayer for Holy Bishops continues with a vision of the restoration of Sion: Et timebunt gentes nomen tuum, Domine, et omnes reges terrae gloriam tuam: quia aedificavit Dominus Sion, et videbitur in gloria sua—“All the Gentiles shall fear thy name, O Lord, and all the kings of the earth thy glory. For the Lord hath built up Sion: and he shall be seen in his glory.” In our own season of cultural and ecclesiastical desolation—the ongoing Passion of the Mystical Body—the revival of Western sacred art, like the revival of the Western liturgical tradition, affords sparks of that divine glory.

Gwyneth would like to thank Mother Teresa Christe and the Marian Sisters of Santa Rosa, as well as Fr. Frank Epperson, Pastor of St. Eugene’s Cathedral in Santa Rosa, California, for graciously making available studio space for this project.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks