Blood & Tears

During the Offertory of the Mass, a little water is added to the wine. This ritual, attributed by most authorities to Our Lord, is interpreted variously.

St. Cyprian writes that the water represents the faithful who are united indissolubly to Christ. In the ancient Roman Rite, the accompanying prayer associates the water with human nature and the wine with the divine nature: “da nobis per hujus aquae et vini mysterium, ejus divinitatis esse consortes, qui humanitatis nostrae fieri dignatus est particeps—grant that by the mystery of this water and wine, we may be made partakers of His divinity who vouchsafed to become partaker of our humanity.” The water’s absorption by the wine thus at once recalls the Word’s assumption of human nature and symbolizes man’s divine adoption and sanctification. In a few moments, the water made wine will become the divine Blood of the Godman. It is no surprise, then, that St. Thomas Aquinas, among others, cites the Patristic association of the water and wine with the water and blood that flowed from the side of Christ (Jn 19:34).

Reflection on Our Lady’s role in her Son’s sacrifice suggests another, complementary interpretation of the ritual of the Offertory water. At the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple, Simeon had prophesied to Mary that “thy own soul a sword shall pierce” (Lk 2:35). For a suffering “longer and greater than all the martyrs,” she is known as Queen of Martyrs, and the liturgy solemnizes the veneration of Seven Dolours of Our Lady especially in two feasts intimately linked to Our Lord’s Passion: on the Friday before Good Friday and on the day following the Exaltation of the Cross. Dom Guéranger, in his entry from the Liturgical Year for the Feast of the Seven Dolours on the Friday of Passion Week, writes that on the Cross, “an ineffable union is made to exist between the two offerings, that of the Incarnate Word, and that of Mary; the Blood of the divine Victim, and the tears of the Mother, flow together for the redemption of mankind.” Our Lord offers His Blood; Our Lady offers her tears. The two offerings flow together, but because of the intimate union between Our Lord and His Mother, their source too is in a certain sense one. In her apparition to St. Brigid of Sweden, Our Lady recalls that “when He looked down at me from the Cross, and I looked up at Him, tears streamed from my eyes like blood from veins. . . Therefore I boldly assert that His suffering became my suffering, because His Heart was mine.” From the one Sacred and Immaculate Heart flow tears and blood. Perhaps the mixing of water into the Offertory wine recalls this mystery of Our Lady’s com-passion.

The mystical union between Our Lady’s sacrifice of tears and Our Lord’s sacrifice of blood is the subject of a new painting of Our Lady of Sorrows by sacred artist Gwyneth Thompson-Briggs.

Concept & Challenges

When Gwyneth began the project, her foremost question was how to manifest an essentially interior Passion. Since all sacred art aims to reveal the spiritual through line and color, the problem of how to show an interior state was nothing new, but Our Lady’s modesty and dignity made depicting her sorrows a special challenge. “I very much wanted to preserve the veil over Our Lady’s sorrows, not to transgress the sacred precincts, so to speak.” Her initial concept was of something almost universally dark in key, with only pools of light on the face, hands, and heart. From the beginning, she knew the brightest area in the painting would be the traditional iconography of Our Lady’s Immaculate Heart pierced with seven swords, one for each of her sorrows:

- The Prophecy of Simeon

- The Flight into Egypt

- The Loss of the Child Jesus in the Temple

- The Meeting of Mary and Jesus on the Via Dolorosa

- The Crucifixion of Jesus on Mount Calvary

- The Piercing of the Side of Jesus with a spear, His descent from the Cross, and the Mary’s Reception of His dead body in her arms

- The Entombment of Jesus

The other major stylistic challenge was how to strike a balance between the Boston School and the Baroque. “As a student of Boston School master Paul Ingbretson, I am fascinated by the play of natural light on skin and fabric, and I wanted to capture effects of light by working with a live model, but I also wanted to paint an Our Lady of Sorrows, not a Portrait of a Lady in the Costume of Our Lady of Sorrows.”

St. Pius X, in his encyclical Tra le sollecitudini, sets forth three essential attributes of sacred music: artistic merit, universality, and holiness—that, is, clearly set apart for divine worship rather than mundane. Gwyneth thinks those attributes are a good measuring stick for sacred art, too. “Boston School works are true art and have universal appeal, but they are distinctly secular. The subject matter is usually scenes of contemporary life, but the stylistic approach too is of this world. Boston School artists try to find poetry through strict adherence to the observed phenomena of light. Their motto is ars aemula naturae—art is nature’s rival, an idea ultimately derived from Aristotle’s definition of art as mimesis (imitation) in the Poetics.” As a sacred artist, Gwyneth takes as her motto, ars perficit naturam—art perfects nature. “Thomas says that grace perfects nature. The observation and emulation of nature is very important for the sacred artist, because grace does not destroy nature. But the sacred artist must endeavor to reveal not merely fallen nature, but also the operation of grace in nature.” The sacred artist does this by perfecting or transfiguring his observations from nature. In this way, sacred art is set apart from the merely naturalistic and attains Pius X’s attribute of holiness.

Gwyneth thus sought ways to transfigure her observations and situate her painting in the tradition of Western realist sacred art. In particular, she sought a balance between capturing natural effects of light and the more imaginative lighting of the Baroque era. “Transfigured light is a powerful tool for conveying the supernatural,” says Gwyneth. Rooted in salvation history, including the Hebrew concept of the kabod (glory) of the Lord and the Transfiguration of the Incarnate Word, transfigured light “is integral to the tradition of sacred art, from the gold mosaics of the Hagia Sophia to the stained glass of Chartres and the chiaroscuro of Caravaggio and Zurbarán.”

Artistic Sources

One of the chief inspirations for the painting was a book on 17th century Spanish polychrome sculpture, The Sacred Made Real. “The painted sculptures most Americans know are the mass-produced, kitsch statues that proliferated in our churches and homes in the 19th and 20th centuries. There is certainly a range of quality among these works, but they all pale in comparison to the religious sculpture of the Spanish Baroque. In addition to being masterpieces of the emulation and the perfection of nature, the works possess an interiority that invites mental prayer. They are born from and at the service of devotion.” In 17th century Spain there were at least two types of the sorrowful Mother: the Our Lady of Sorrows proper, in a blue mantle, and the Our Lady of Solitude, a depiction of Our Lady in mourning after the death of her Son. Later depictions sometimes combine the two types.

One later image that continually influenced Gwyneth’s work was a study by John Singer Sargent for his Virgin of Sorrows at the Public Library in Boston. Sargent, who copied every Velázquez in the Prado, was famous as a portraitist, but the Virgin of Sorrows is part of an imaginative mural on the history of religion at the Public Library in Boston. “It’s quasi-sacred,” says Gwyneth.

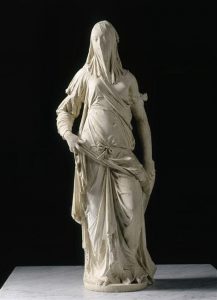

She was also inspired by avowedly secular artworks: Antonio Corradini’s Veiled Lady in the Louvre and Japanese yamato-e ladies in layer after layer of kimono. “I remember standing in awe before the Corradini; through his technical brilliance, the veil reveals, rather than conceals, the lady. In my work, I wanted the veil to reveal not the body but the soul.” This is something she sees in the Japanese tradition of hikime kagibana, where the features of the face are rigidly stylized or elided, and instead fabric and gesture reveal personality.

Preparation

Gwyneth elected to dress her Lady in black to express the depths of her desolation and in copious silver lace to suggest regality and tears. “I wanted to be restrained in depicting actual tears. The sinuous lace is something like an objective correlative of her sorrows, an exterior expression of her interior torment.” The lace is also a reference to Spanish Madonnas, as well as to altar linens, both those on which the Passion is renewed, and the linens of the Temple where Our Lady spent her youth, by tradition doing fine needlework. “There is something delicate, feminine, and essentially hidden about fine lace. One must be very close to appreciate its complexity. The fine stitching of the altar, which is traditionally made by nuns in imitation of Our Lady, is visible only to the priest and to God. It is almost a love letter between the soul and Christ. I wanted to suggest all of that by choosing lace for Our Lady of Sorrows.”

The sacrificial lace and jet black of mourning are set against burgundy damask suggestive of penitential vestments and the Precious Blood under the appearance of wine.

After a couple of concept sketches, Gwyneth’s first tasks were collecting fabric samples, finding a model, and testing the fabric with the model. “People are often surprised to learn that modeling doesn’t involve posing for a few photos, but sitting for hours, in fifteen-minute increments,” says Gwyneth. The camera can never take in as much information as the human eye; it always distorts and simplifies the light.” She tried various combinations of fabric to build up layer upon layer of mantle. “I wanted to convey the weight of the sorrow by suggesting the weight of Our Lady’s garments.”

She and the model worked out a dignified seated pose, with the hands folded in the lap. “Grief disfigures,” Gwyneth explains, “but in depicting Our Lady, one never wants her to lose her beauty. Unlike Christ, whose beauty was masked by His brutal Passion, Our Lady never lost her beauty as she suffered with Christ. I wanted to convey her regal beauty in the midst of sorrow.”

Once the fabric and model were arranged, Gwyneth completed a study in charcoal and white chalk.

The Painting Process

She began by toning the canvas with burnt umber to start from a greater unity of darks. “That’s a Baroque trick. Velázquez almost always began by toning the canvas. It’s anathema to the Boston School, because a white canvas allows pigments to retain their highest chroma. I wanted to lower the chroma of the painting, in order to provide the greatest possible contrast with the flaming heart.” Next, she blocked in large areas of color while painting from life.

As she proceeded, Gwyneth realized that the original pose, with the model seated with hands folded in her lap, failed to convey the dynamism of grief. “It was too static. It was veering towards the Portrait of a Lady in the Costume; I had to increase the dynamism without disfigurement or melodrama.” She separated and extended the hands, introducing a long diagonal opening in the veil and contrasting diagonals in the newly opened right hand. She also suggested diagonals in the burgundy background. “Diagonals, like the weapons that often produce them, communicate violence—here, the emotional violence done to Our Lady’s heart.” The gesture also subordinates the face, as in the yamato-e tradition. By relying on gesture, fabric, and color to convey grief, Gwyneth was able to keep the face regal and contemplative.

Working with the model for two-hour blocks, broken into fifteen-minute sessions with three-minute breaks, Gwyneth tried to develop the various areas of the painting simultaneously, “fifteen minutes on one hand, fifteen on the face, fifteen on a section of cloth, etc.” This was critical in order to evaluate and correct colors and proportions in relation to each other. In total, the model posed for ten hours. After a string of overcast days, one sunny day “ruined everything” because the light was so different. “Most of my work that day had to be wiped out.” Ideally, says Gwyneth, one has a sunny day painting and a cloudy day painting. “That’s one of the advantages of the still life.”

After each block with the model, Gwyneth reviewed the entire composition, wiping out anything that needed to be redone and letting successful passages dry a bit. Some drying is necessary to achieve black blacks and for lighter passages. Otherwise, the application of fresh paint tends to pick up underlying layers and make the area fuzzy. She also checked the painting under different light, at different distances, and even in a mirror. “Since the mirror reverses everything, your brain registers the image as if for the first time—it’s a very useful trick for noticing otherwise elusive errors.”

When working with a model for sacred art, one risk is producing too close a likeness. Gwyneth is emphatic that sacred art should never bear a recognizable likeness to models, “unless you are fortunate enough to have a saint sit for his own portrait.” This would be merely copying nature, rather than perfecting it. There is also a practical reason: “You should never be distracted from prayer by recognizing the model.” Practically speaking, this meant blocking in the larger shift in light with the model, but then using other faces and hands (from life and from art) to adjust the features. The hands passed from nature through Mannerist elongation into the 15th century Flemish tradition. Their ultimate inspiration were the hands of Christ in the Pietà of Villeneuve-lès-Avignon by Enguerrand Quarton. In Our Lady of Sorrows, the expressiveness of the hands contrasts with the reserve of the face, heightening the sense of interior torment.

For the lace, Gwyneth chose a dry brush on canvas technique. Fairly stiff oil paint is applied to the brush, so that when the brush is skimmed across the textured canvas, the line of paint is not perfectly smooth, allowing the base colors to come through. This gives a lifelike variation in color especially suitable to layered fabric.

Gwyneth kept the modeling on the face somewhat dark and subtle, saving the high contrast for the lace and especially the heart, which she also built up with the impasto technique of thick strokes of paint. “Ultimately, this work is about the sorrows of Our Lady’s heart, so everything else had to be subordinate to it in value.”

After a few days’ drying time, Gwyneth added details with a small brush, including a single tear.

The Finished Painting

Our Lady of Sorrows was completed two days before Ash Wednesday 2019. 24 inches by 34 inches tall, it is suitable for hanging in a side chapel, oratory, rectory, or retreat center.

The finished painting unites the Boston School observation of natural light on the skin with more imaginative elements, including loose, suggestive modeling, especially in the background, and the sparkle of the tear-like lace. Despite the violence of the pierced heart, the diagonals, and the contorted hands, Our Lady’s com-passion here is essentially contemplative. The swords are small—perhaps suggestive of nails—and simplified. Much of the face is lost in shadow. The heart itself is partly veiled.

After her second sorrow, the loss of the Child Jesus in Jerusalem, St. Luke records for the second time that Mary “kept all these words in her heart,” contemplating them (Lk 2:51; cf. Lk 2:19). Dom Guéranger emphasizes that Our Lady stood by the Cross (Jn 19:25): “The sacrificing priest stands, when offering at the altar; Mary stood for such a sacrifice as hers was to be.” Our Lady of Sorrows communicates both the contemplative suffering and the sacrificial solemnity of Mary, inviting the viewer to join her in offering a sacrifice of tears.