He hath led me, and brought me into darkness, and not into light.

—Lamentations 3:2, chanted in the Office of Tenebrae for Good Friday

Catholic philosopher Josef Pieper, in an essay first published in 1952, writes that “man’s ability to see is in decline” because of “visual noise.” By sight, Pieper does not mean “the physiological sensitivity of the human eye,” but rather “the spiritual capacity to perceive the visible reality as it truly is.” Perhaps, however, our declining vision is both spiritual and physiological. If we accept the premise that matter does not reveal spirit (as both materialists and gnostics do)—if sight cannot unlock the mystery of being, but only appraise commodities—why bother really to look at things? Our eyes follow our souls into sloth.

To strengthen our sight Pieper suggests fasting and abstinence from “visual noise” and creating art. “The mere attempt,” he writes, “to create an artistic form compels the artist to take a fresh look at the visible reality.” Sacred artist Gwyneth Thompson-Briggs agrees with Pieper that making art improves our ability to see. It is one of the reasons she regularly teaches drawing classes. In this season of fasting and abstinence, Gwyneth offered a three-part drawing workshop for twelve students at St. Francis de Sales Oratory, the St. Louis apostolate of the Institute of Christ the King Sovereign Priest.

Why Drawing Matters

“Drawing is the most basic kinesthetic aid to learning to see,” Gwyneth explains. “You need only a pencil, paper, and a well-lit flat surface to draw on.” Yet it can be deceptively simple. Self-taught draftsmen often develop bad habits that limit their ability to see or render reality accurately. “That’s why traditional artistic instruction is so important.”

Gwyneth emphasizes the world “traditional.” “When I was in art school and the instructor was coming around giving critiques, the standard response was, ‘well, I intended that; I like it that way,’ and the instructor would usually nod and move on.” Gwyneth thinks that is an unhealthy approach to art and to life. “Imagine that I run over somebody and a policeman comes to apprehend me and I tell him, ‘well, I intended that; I like running over people.’ That wouldn’t prevent me from being booked—and it shouldn’t! The nature or moral value of things is not up to me. It should be the same for the artist: he has to learn to perceive and represent what is, not merely what he feels like. Feelings that aren’t guided by the light of reason perceiving reality don’t free us; they imprison us.” A traditional art instructor helps his student to perceive and render natural forms as accurately as possible.

Since seeing and rendering even a turnip can be overwhelming, artists have long broken up the task into parts. Art distinguishes, for instance, the questions of line, value, and color. Drawing usually brackets the question of color so that the artist can focus on attaining right proportion between the lines and planes of his subject. Bracketing color is so useful for attaining right proportion that until the 20th century, almost all paintings began with extensive drawings. “Color is much less forgiving than lines or shadows. It’s much easier to move a line in a drawing, or adjust shading, than to remove a complex arrangement of color,” says Gwyneth. In short, drawing is the most basic skill for any visual artist.

The Workshop

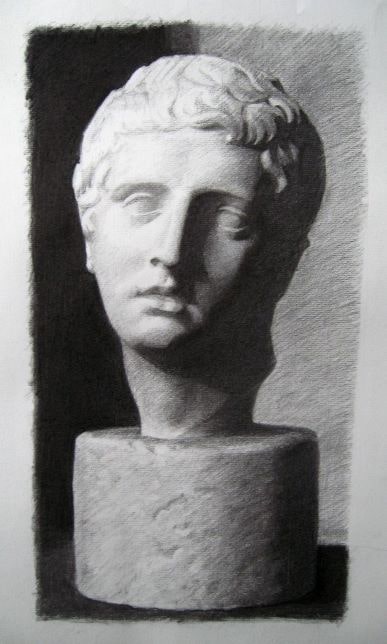

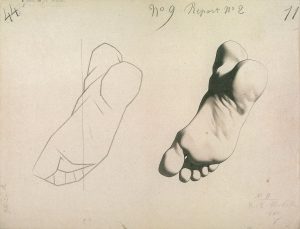

Gwyneth structured her drawing workshop this Lent around a collection of cast drawings by 19th century Academic painters Charles Bargue and Jean-Léon Gérôme. The two painters designed the drawings to be copied by first-year art students. Drawing from plaster casts of antique and Renaissance sculpture was a standard component of art academies until it was set aside in the 20th century. Today, cast drawing only remains foundational in classical ateliers like that of Paul Ingbretson where Gwyneth trained. (Ingbretson himself is in the artistic lineage of Gérôme: Gérôme taught William Paxton, Paxton taught R. H. Ives Gammell, and Gammell taught Ingbretson.)

Ivory-colored casts simplify the artistic challenge by omitting the question of color and revealing shadows. The student, however, still has to translate three-dimensional reality into two dimensions and cope with changing light conditions. Copying from master copies of casts further simplifies the visual information. “Plus,” says Gwyneth, “you’re seeing reality through the eyes of masters. These drawings reveal nuances of light and shadow that would be lost to most eyes. It’s an ideal starting place, but challenging enough to benefit even advanced artists.”

Gwyneth also uses the Bargue collection because of the beauty of the subject matter. “It’s theoretically possible to copy master drawings of plastic bags, but copying from antique casts is much more ennobling.”

Meeting for three two-hour sessions, students completed a single drawing. “Six hours is a bare minimum for this exercise. I strongly encouraged students to spend time working on their drawings outside of class.”

The First Class: Proportion

In the first class, after introducing the history and theory behind cast drawing and master copies, Gwyneth explained the proper way to use a pencil. “The first rule of drawing is, sharpen your pencil!” Without a sharp pencil it is impossible to achieve the lightness and fluidity of line needed for accurate and attractive drawing. Gwyneth then showed students the advantages of grasping the pencil at its midsection. “For writing, most people hold a pencil very close to its tip. This limits the range of motion. For drawing you want a broad range of motion, pivoting more from the elbow than the wrist, so that the pencil becomes an extension of the forearm rather than of the hand.”

Pencils sharpened and correctly grasped, the students were ready to learn how to draw a line. “Most people have this idea that drawing involves sketchily petting the pencil across the paper, rather than smooth, unbroken strokes. Ugly strokes make for an ugly drawing, no matter how accurate the proportion.” Instead, Gwyneth teaches students to boldly make their best attempt and correct the entire line if it is off. “Drawing well requires a boldness, but also a lightness of touch.”

The students began with a short exercise: drawing a circle with a single line. After the initial attempt, each student identified and corrected one mistake at a time, working from biggest to smallest, until the circle’s proportion was close to perfect. “Always work from your biggest mistake down; don’t get lost in the small errors until the big ones have been corrected, or you may end up having to lose all of those corrections themselves when you turn to an underlying problem.”

Gwyneth also discussed tools for identifying errors in proportion: looking at the drawing from a distance or in the mirror, or asking a classmate for a critique.

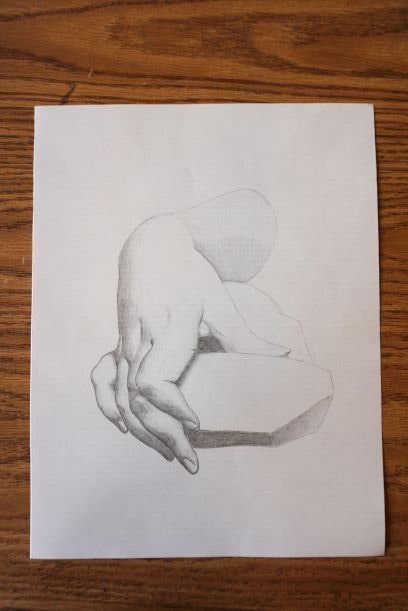

Students then chose a cast drawing to copy and spent the remainder of the class working on an outline of the whole drawing.

The Second and Third Classes: Value and Finish

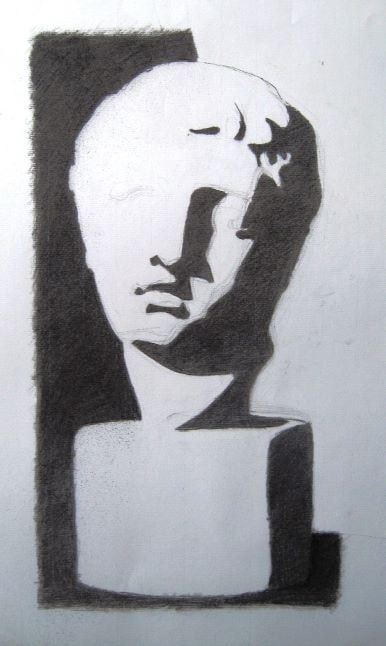

In the second class, students began working on the interiors of their copies. First, they blocked in the shadow shapes—the outlines of the major shadows—according to the drawings supplied for this purpose next to the completed cast drawings by Bargue and Gérôme.

Gwyneth discussed the distinction between cast shadows and form shadows, and the hierarchy of shadows. “Value is the technical term for relative light or darkness. In a cast drawing, since you are working with only one hue—the gray of your pencil—the gradations of light of dark become much easier to see than when working from a variety of hues.” Students began by drawing in the darkest shadows, but as lightly as possible. Instead of pressing down on the pencil to produce dark lines, students learned to apply light strokes in layered glazes.

In the third class students worked on refining the transitions from light to shadow and controlling the beauty of the finish. Gwyneth also discussed next steps for aspiring artists: the study of anatomy, perspective, art history, still life, and color theory. She also shared some of her own drawings to show how the cast drawing exercise translates into drawing the figure from life.

Drawing in Lent

Though she did not intend the course as particularly Lenten, Gwyneth sees parallels between copying a master drawing and the Lenten battle. Lent is the privileged time of year for imitating Christ, ‘the image of the invisible God’ (Col 1:15). In particular, in Lent we imitate Christ’s forty-day fast in the desert. We withdraw from the pleasures of life in order to identify our vices, combat the devil, and grow in virtue. “When you dedicate hours to a master copy, you are staring at a little piece of reality and trying to conform to it. You see your faults, fight against them, and, little by little, approach the original.” As we approach the Paschal triumph, when the light of Christ will illumine the darkness that seems this week to extinguish it, perhaps those will see best who have spent this Lent drawing.

Gwyneth would like to thank Reverend Canon Michael K. Wiener, Rector of St. Francis de Sales Oratory, for graciously supplying facilities for the workshop.

Lead images: (L) the second stage of a cast drawing: blocking in the shadows ; (R) the finished drawing by Gwyneth Thompson-Briggs.