Deposuit potentes de sede, et exaltavit humiles.

He has put down the mighty from their seat, and exalted the lowly.

—Luke 1:52

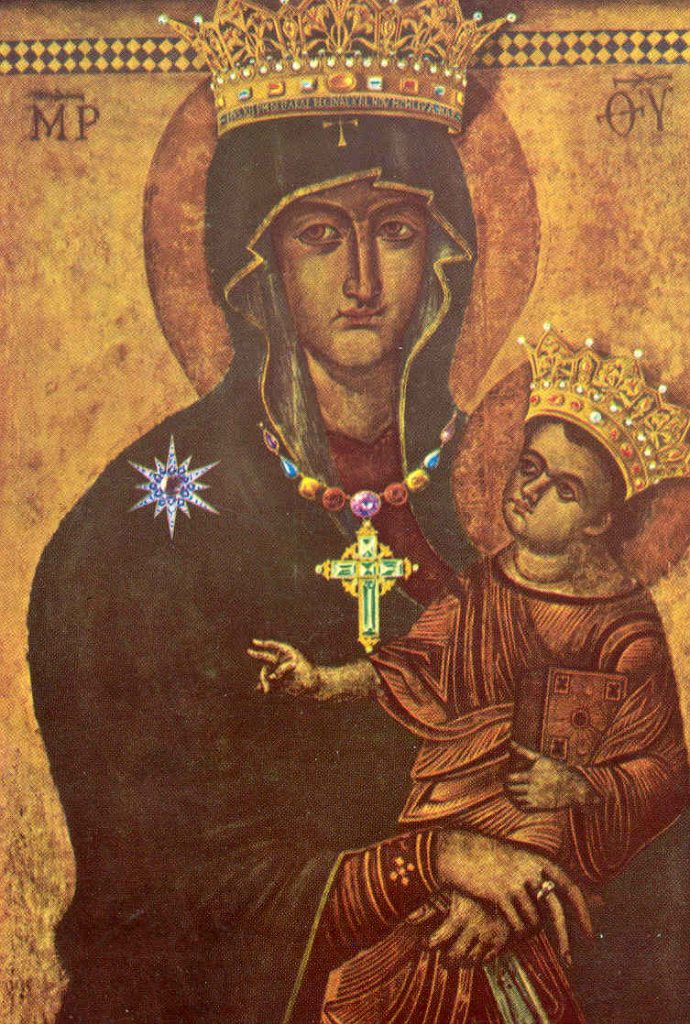

Tradition attributes several paintings and sculptures of Our Lady to St. Luke, among them the Salus Populi Romani, which Pope St. Gregory the Great carried in procession during the plague which ravaged Rome in 590, and the original, Spanish Virgin of Guadalupe. The evangelist and patron saint of artists also crafted an exquisite portrait of Our Lady in the first two chapters of his Gospel, which provide many details unavailable elsewhere.

Twice St. Luke states that Our Lady “kept all these words in her heart.” After the adoration of the shepherds, who have recounted the words of the angels announcing and singing the praises of the Savior’s birth, Luke tells us, “Mary kept all these words, pondering them in her heart” (2:19). Twelve years later, after the boy Jesus is found in the Temple and asks whether Mary and Joseph did not know “that I must be about my father’s business,” we are told that “they understood not the word that he spoke unto them” but that “his mother kept all these words in her heart” (2:49-51). Luke’s repetition draws attention to both episodes, where Our Lady meditates first on the words of angels and then on the words of her Son. In the clarity of her Immaculate Heart, free from the darkening of the intellect that accompanies sin, the Seat of Wisdom nonetheless pondered over the words of angels and kept the inscrutable words of the Lord.

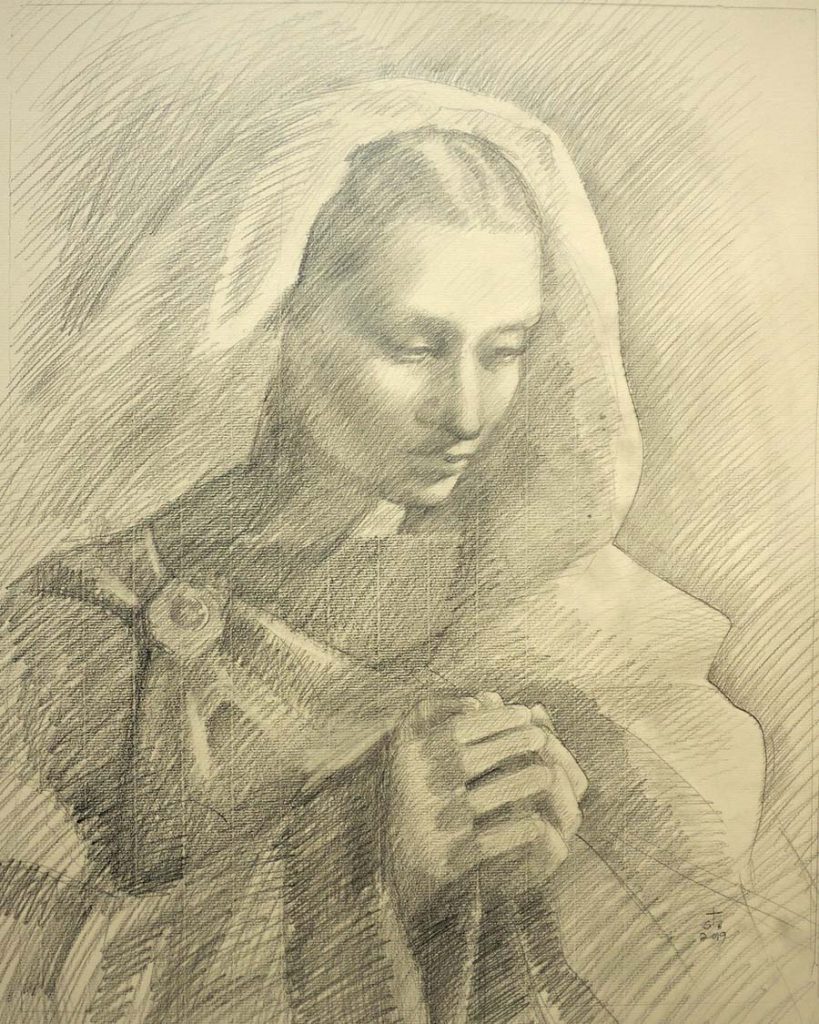

The extraordinary humility and interiority of the Blessed Virgin attested by these verses is one of the themes of a new Madonna by sacred artist Gwyneth Thompson-Briggs. Stylistically indebted to the 17th century Marian devotional images of Giovanni Battista Salvi da Sassoferrato, particularly his Madonna in London’s National Gallery, Gwyneth’s Madonna also incorporates brushwork inspired by Titian and drapery influenced by 15th century Flanders.

“The Sassoferrato Madonnas are studies in regal interiority. Beneath her lapis lazuli robes and her flawless classical face, the Virgin is always deep in mental prayer,” says Gwyneth. “I wanted to portray the same idea: the exaltation of the humble of which Our Lady sang in her Magnificat, and the beatific repose of dwelling in perpetual contemplation of the Word.”

Preparing to Paint

Relying on the National Gallery Madonna as a concept sketch, Gwyneth began by securing fabrics and a model. Then she completed two three-hour graphite sketches with the model. After seeing the first sketch, the patron asked for a more dramatic inclination of the head. “The greater the angle of the head, the greater the challenge of convincingly rendering the foreshortening,” says Gwyneth. Thus, there was less latitude for the model to move her head during and between poses. “Fortunately,” Gwyneth says, “I was working with an excellent model. The dramatic inclination forced me to improve as a painter.”

Gwyneth also completed a color study with the model. She describes the colors, inspired by Sassoferrato, as “the bluest blue and the reddest red.” To achieve their chromatic intensity, Gwyneth used combinations of a saturated, opaque hue overpainted with a saturated, transparent hue. She chose cobalt blue topped with ultramarine and cadmium scarlet topped with alizarin crimson. Other hues were added where necessary to convey the effects of light. In Sassoferrato’s day, ultramarine was extremely costly, because it was made from ground lapis lazuli imported from Afghanistan. It tended to be reserved for sacred figures, especially the Blessed Virgin. The pigment became much more widely available in the 19th century when a synthetic alternative was developed. “I think you can tell the difference,” says Gwyneth. “It’s still a lovely color, but it does not have quite the same splendor.”

After completing graphite and color studies, Gwyneth stretched and gessoed her canvas and transferred her composition from the second graphite study using homemade charcoal paper. She prefers using charcoal to graphite for transferring designs because of its lack of wax. “Charcoal erases very easily,” Gwyneth explains, “and mixes with the surface of the oil paint. It’s more delicate, leaving no distracting lines underneath.” After transferring the design, Gwyneth went over the lines with a bit of watercolor. “It’s more permanent than charcoal, but not as harsh as graphite,” she says. Next Gwyneth blocked in broad areas of neutrals.

Painting with Drapery and Model

Gwyneth began to paint the drapery first. She built a mannequin and carefully placed fabric to create sumptuous folds. “The drapery is crucial because it conveys the transfigured state of Our Lady as Queen of Heaven,” says Gwyneth. “This is very far from a historical depiction of a poor woman from Galilee. Her humility would come into play in the face and hands, but in the drapery, I sought to convey only glory.” In preparing and painting the drapery, Gwyneth looked to Flemish paintings by Jan van Eyck and Rogier van Weyden. “There’s this wonderful Northern Renaissance sense of gravity acting on fabric, she explains. “It conveys both the luxuriance of the materials, but also the perpetuity of heavenly glory. They dipped their fabrics in starch to keep them in place; I simply painted them without a live model.”

After developing the fabric on the canvas, Gwyneth brought back the model and worked directly from her to paint the face and hands. Between sessions with the model, Gwyneth idealized from imagination. “I think that’s the only way not to paint a portrait. You have to paint without the model in front of you,” says Gwyneth. “Then, when it starts to look unnatural, you use the model again to bring it back to nature. The goal is not to disfigure, but to transfigure. As a painter of sacred subjects especially, I’m aiming for a supernatural beauty, not an unnatural beauty—which is another name for ugliness anyway.” Gwyneth’s method was taken for granted in the Renaissance and Baroque eras, but is rare today. “On the one hand, there are artists who are trained in classical realist ateliers to paint like the French academics. They simulate nature, without surpassing it. On the other hand, there are artists who are convinced that only Byzantine distortion is legitimate for sacred art. There are very few trying to strike the Renaissance and Baroque balance. That’s what I’m trying to do, and trying to encourage young painters to rediscover,” says Gwyneth.

In modeling her paints, Gwyneth departed from Sassoferrato, turning to Giorgione and his pupil, Titian. “Sassoferrato used a heavier application of opaque paint,” explains Gwyneth. “I became interested in varying the opacity and layering the paint in several levels. It’s a technique developed especially in Venice in the 15th century, and brought to mastery by Titian in the 16th. The paint quality trades some of the gemlike nature of a smoother surface for a much more sophisticated rendering of light.” The technique is especially suited to rendering lace, which Gwyneth chose for the Madonna’s veil in another departure from Sassoferrato.

The Triumph of Humility

For the hovering crown of roses, a reference to the symbolism of Mary as the Mystical Rose, Gwyneth used a single rose posed to catch the light in various ways. “Our Lord wore a crown of thorns; it seems appropriate for Our Lady, who interiorly shared in His Passion and now shares in His Triumph, to wear a crown of roses,” she says. When the patron vetoed the rose crown, Gwyneth painted over it and tried a crown of stars. When that crown also failed to please, Gwyneth removed the wettest layer of paint, revealing the remnants of the rose crown. “I really liked the almost spectral appearance of the roses when they came back from oblivion,” she recalls. The patron did not, so Gwyneth painted them out again and introduced the suggestion of a halo. “Fortunately, at that point it became apparent that the patron and I had different visions.” She was concerned about overworking the painting, so she approached him about completing the painting on her own. “It was very amicable, and I think fortuitous,” she says. Gwyneth quickly removed the halo, restoring the rose crown a second time. “I added a little more paint, but essentially the effect comes from painting it out twice. It’s a much more complex image than it otherwise would have been.”

As a final highlight, Gwyneth included a brooch on Our Lady’s mantle. “It’s meant to be lapis lazuli set in gold,” she says—a reference to Sassoferrato’s ultramarine. Gwyneth also intended the brooch to reference the jewels that have been offered to images of Our Lady by the faithful over the centuries. “Today there is a trend to denude images of Our Lady of their ornaments. I was so sad to learn that the Salus Populi Romani was stripped of her crown and jewels in the 1980s. I wanted to do something to rectify these attacks on Our Lady’s exaltation,” Gwyneth says. “As she herself put it in her Magnificat, God ‘hath regarded the humility of his handmaid . . . He hath put down the mighty from their seat, and hath exalted the humble’ (Lk 2:48-52). What God has exalted, we must exalt too. I hope my Madonna conveys the same expression of the triumph of humble prayer.”