“I will be as the dew, Israel shall spring as the lily, and his root shall shoot forth as that of Libanus.”

Osee 14:6

In his principal Mass, St. Joseph is compared to three plants: the palm, the cedar of Lebanon, and the lily. The Introit begins, “Justus ut palma florebit: sicut cedrus Libani multiplicabitur—The just shall flourish like the palm tree: he shall grow up like the cedar of Libanus,” applying Psalm 91:13. The Alleluia concludes, “Justus germinabit sicut lilium: et florebit in aeternum ante Dominum. Alleluia—The just shall spring as the lily; and shall flourish forever before the Lord. Alleluia,” adapting the text of Osee 14:6. All three comparisons—the flourishing palm, the broad-growing cedar of Lebanon, and the springing lily—were on the mind of sacred artist Gwyneth Thompson-Briggs as she conceived her new painting of St. Joseph, but chiefly the lily.

“At side altars dedicated to St. Joseph over the years, I’ve always been intrigued by the paradox of the humble carpenter holding a rod flowering with sublime lilies.” The painting, she says, grew out of reflection on the coincidence of humility and sublimity in St. Joseph. “I knew the lily would be prominent.”

Conveying Humility

Though he is entrusted with the Mother of God and with the Divine Infant Himself, St. Joseph never speaks in Scripture, and he was largely neglected in the Patristic and early Medieval eras. The Legenda aurea, an influential 13th century collection of hagiographies, contains no entry for St. Joseph (though he is discussed in entries dedicated to the feasts of Our Lady). It was only during the Counter-Reformation, partly through the devotion of St. Teresa of Avila, that he became ubiquitous in Catholic worship and imagination.

“His silence in Scripture and his long neglect in public worship speak to his humility. Though he is the head of the Holy Family, he never usurps the glory belonging to the Blessed Virgin and Her Son.” Thus, says Gwyneth, St. Joseph exemplifies true Christian headship, which never acts on its own initiative, but only as the executor of the divine will. “St. Joseph is a model for the Christian father, but even more so for the pastor, bishop, and Pope, all of whom must never speak a word of their own, but rather protect, promote, and enact the words of Mary and Jesus. Before the Incarnate God, the Immaculate says only, ‘Do whatever He tells you,’ but we sinners must imitate St. Joseph’s complete silence.”

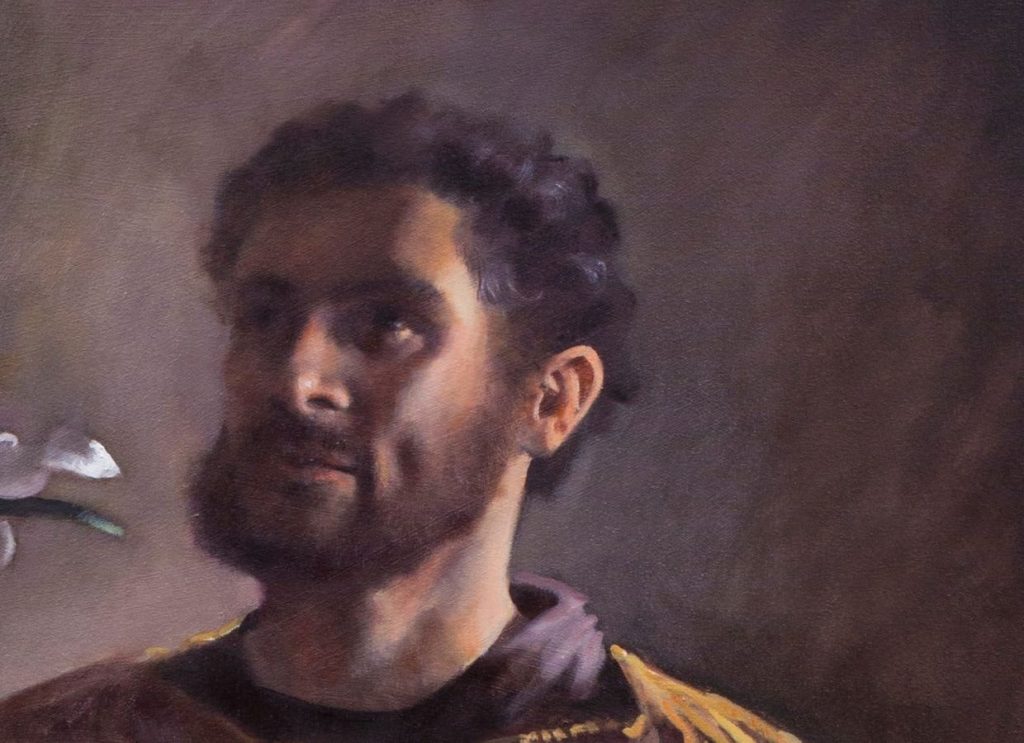

The visual correlate of silence is shadow. “I decided to cast St. Joseph’s face in shadow,” says Gwyneth, “both to express his humility and total lack of vanity, and also to allow each viewer to complete the face of St. Joseph according to his or her own meditations.” St. Joseph’s prominence only emerged over the course of centuries, and the face of Gwyneth’s St. Joseph only emerges with prolonged contemplation. Instead of the face, the light falls on the ear, suggesting Joseph’s attentiveness to the divine instructions given through angels, through Mary, and through the child Jesus.

The Lily and the Carpenter

Before the shadowed face or illumined ear, however, the first thing the eye registers in the painting is the lily. According to tradition, St. Joseph was chosen as the spouse of the Virgin because his rod, unique among those collected from among the eligible bridegrooms, bloomed with lilies. This was interpreted as a sign of St. Joseph’s purity and consequently of his divine election. The lily is also associated with Our Lady, “the purest of lilies, that flowers among thorns” in the words of the Flos Carmeli, the sequence for the Feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel. In Gwyneth’s painting, Joseph wields the lily-flowering rod with both hands, like a knight wielding a sword or an acolyte processing with a candle. The lily is at once an emblem of virility rooted in purity and of splendor crowning humility.

After the lily, the next thing to register are Joseph’s carpentry tools—a square and a hammer—a reminder of Joseph’s faithful enactment of divine command and of his toil as a working man. “Though he was the spouse of the Queen of Heaven and the foster-father of the King of the Universe, St. Joseph had to earn their daily bread. I wanted to reveal this side of him—that his glory was attained through labor. His calling was to the active life, though of course he must also have been contemplative in the midst of his activity.” Thus Gwyneth sought to give St. Joseph the build of a laborer, rather than of an athlete or a god. This choice—and what is suggested of the face—situate the painting more in the naturalistic tradition of Caravaggio and his followers than in the tradition of Annibale Carraci, the originator of the more classicist trend in Baroque art.

Purity and Virility of the Custodian of Virgins

Gwyneth sought to eschew the 19th century tendency to portray St. Joseph as “soft, even effeminate.” Through the centuries, there have been several solutions to the need to portray St. Joseph’s purity as the spouse and guardian of the ever-Virgin Mary. Byzantine, Medieval, and Renaissance artists often portray him as an old man, grey-haired or balding, even relying on his rod for support. In the late 16th century, after intense consideration of the role and purpose of sacred art in light of the renewed iconoclasm of the Reformers (see, for instance, Joannes Molanus’ 1570 De Historia SS. Imaginum et Picturarum), Catholic artists began to depict St. Joseph in the prime of life at the time of his betrothal to the Virgin and the nativity of the Savior. Thus Joseph’s lifelong purity shines more brightly, like his namesake the Patriarch Joseph, making him a more fitting spouse for the perpetual Virgin. A youthful Joseph was also seen as more practical for a man called to lead the Holy Family into and out of exile in Egypt and to protect the Blessed Virgin until her Son’s majority. In the Industrial Age, St. Joseph is typically depicted with “the cloying prettiness of a porcelain doll,” something Gwyneth sees as totally inappropriate. She elected for a Baroque St. Joseph; “I thought of him as thirty-three.”

Unlike most Baroque depictions, however, Gwyneth sought to create a purely devotional image of St. Joseph alone. The Holy Family image became popular in the 16th century, and Baroque artists continued the Medieval and Renaissance tradition of narrative images of St. Joseph, representing his espousals, his dreams, the Nativity in Bethlehem, the flight into Egypt, the recovery of the boy Jesus in the Temple, and Joseph’s death. Rarely, Baroque artists depict St. Joseph holding the Christ Child. The purely devotional image of St. Joseph alone only becomes typical in the 19th century. “I wanted to rescue the devotional image of St. Joseph from kitsch,” explains Gwyneth. “He is such an important saint, but this wasn’t fully recognized until the 19th century, when sacred art was plummeting in quality, so there is a dearth of truly beautiful depictions.”

The immediate occasion for Gwyneth’s St. Joseph was the first foundation of the Benedictines of Mary, Queen of Apostles, in Ava, Missouri. “When I read that their new home was The Monastery of Saint Joseph,” Gwyneth recalls, “I thought how appropriate it was for these sisters to set off into the wilderness under the protection of Saint Joseph, who protected Our Lady and Our Lord in the wilderness during Herod’s massacre of the Holy Innocents. I was so impressed by the sisters’ faith and worried that they needed a beautiful image to help them meditate on St. Joseph’s protection.” Mother Abbess Cecilia Snell of Our Lady of Ephesus Abbey in Gower, Missouri, graciously accepted Gwyneth’s offer of a painting of St. Joseph for the new foundation.

The Painting Process

Gwyneth began by sketching several concept sketches, working out the basic composition that foregrounds and balances the lily and the tools. Then she tested fabric with different backgrounds, selecting a gold satin tunic because it combined the form of a simple working man’s garment with a fabric that manifests his virtues, divine election, and heavenly glory.

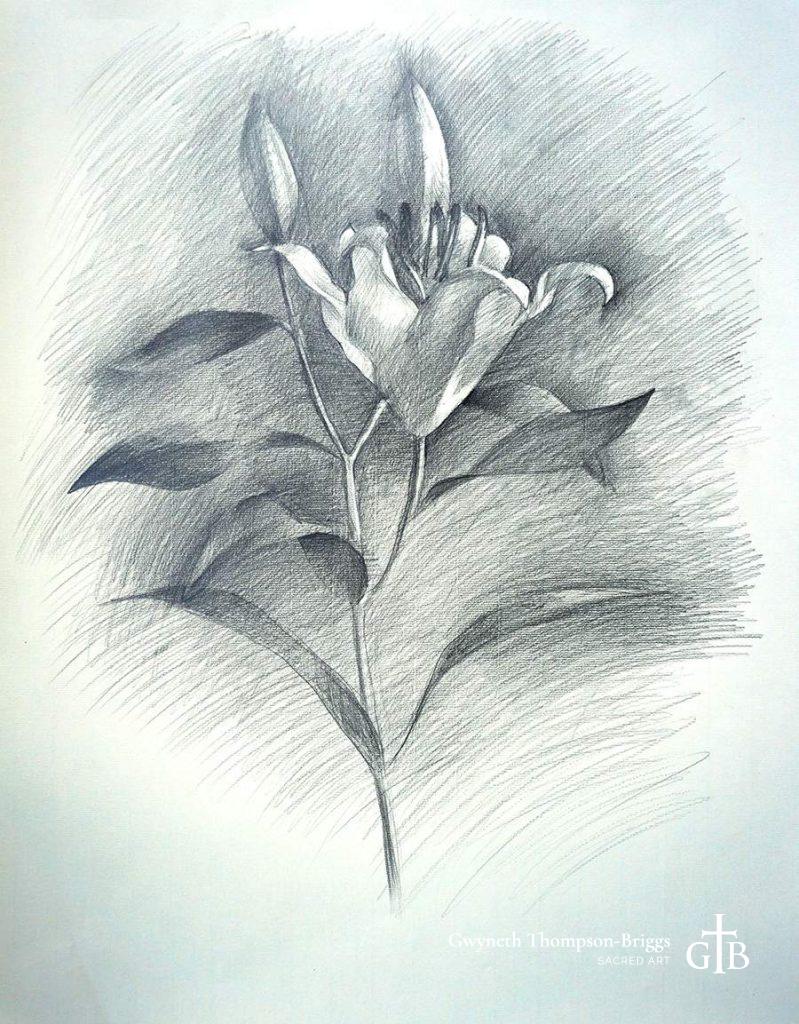

From the start, Gwyneth knew she wanted to work from real lilies, but she knew too that this presented a special challenge. “There is no comparison between real and fake flowers,” Gwyneth says, “but this is especially true of the white lily, whose petals are ever-so-slightly translucent.” She had to work from real lilies, but she would have to work fast, because lilies blossom, unfurl, and fade quickly. The lilies’ mutability was confounded by the midsummer heat in her St. Louis studio.

“As a student in Paul Ingbretson’s studio, we always worked from fake flowers, because they don’t change shape or color, and we were focused on attaining perfection of rendering from life,” Gwyneth remembers. For the devotional image, Gwyneth was less concerned with capturing a particular lily from nature: “In sacred art, the best practice is never to merely imitate a figure from life; there needs to be some idealization so that the viewer can see the sacred and not merely the mundane. In this painting, I did something similar with the lily.” She worked from a succession of flowers as they attained their peak, but she still had to work fast: “I bought the flowers on Thursday; one branch was just beginning to peak and I did a pencil study of it that day. On Friday and Saturday, I painted the branch on the canvas.” Painting the flowers wound up being one of her favorite parts.

Gwyneth also completed a pencil study of the figure from one of her two models. Initially, she had intended to have the hands clasp the rod as in prayer, but she realized during the study that the firmer grasp was more effective for communicating Joseph’s vitality. The bare forearm became a principal feature of the image.

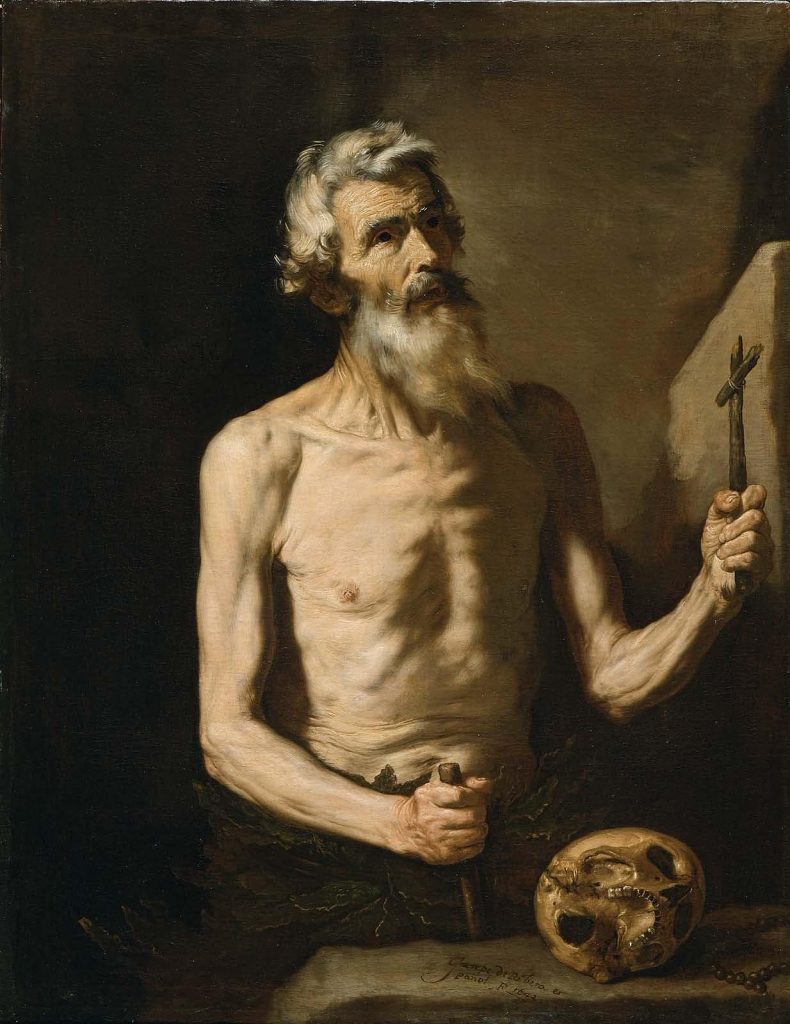

For the light scheme, Gwyneth was inspired by a painting of St. Onophrius by Ribera that hangs in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and which she had copied in person. “When I copied Ribera’s Onophrius, I was struck by how the highest detail and texture was located at the edge of the division between light and dark, with much obscured in the shadow, of course, but also with a more subtle blurring further from the division line.” The light source in the Ribera is the upper left; Gwyneth reversed this for St. Joseph.

After painting the flowers, she began painting the figure, then painted the tools before completing the figure. One of the last parts to be completed was the forearm, where Gwyneth alternated warm and cool tones in the same patch of light, lending a greater liveliness to the whole. “The skin is not monochromatic,” Gwyneth explains, “even where it is lit evenly; it always possesses variation produced by subtle gradations of form, but also by the blood—variously blue and red—coursing beneath it. When a painting doesn’t capture this variation in hue, the figure can appear more statuesque than alive.”

From Model to Saint

One of the greatest challenges Gwyneth faced was translating models she knew well into a saint recognizable to all Christians. She chose her principal model because she perceived humility in his face and bearing. “Normally,” says Gwyneth, “form, color, and movement do reveal something of the virtues and vices of the sitter. But of course the artist has to draw this out.” Gwyneth’s task, however, was not merely to reveal and emphasize the humility she perceived in her model, but to transcend her model altogether, taking the manifestations of his real virtue as clues towards the appearance of one of the greatest of saints. “There’s always an anticipation of the life of glory in sacred art,” she sums up. “We peer through a glass darkly and try to discern what will only be clear in paradise.”

St. Joseph is depicted life-size, the ideal for figure-painting because it is at once the most comfortable to paint and the most natural for viewing. “Since we are used to encountering life-size figures in nature, we tend to perceive life-size figures in art as more real, more present, than figures painted under or over life-size,” Gwyneth explains. In total, the painting measures 30 x 40 inches.

Gwyneth does not know where the Benedictine Sisters of St. Joseph Monastery will place the painting, but she intended the image to be viewed from a kneeling position under low lighting conditions—candles or natural light—in a chapel, with a distance from ten to thirty feet. Especially at that distance, the face is shrouded in mystery, the arm and tools clear, and the lily brightest of all, so that Gwyneth’s St. Joseph truly “springs forth as the lily.”

Updates

St. Joseph has arrived safely with the Benedictines of Mary Queen of Apostles in Gower, Missouri.

Unveiled on the occasion of four first professions and five investitures, St. Joseph is still destined for the Sisters’ new foundation, St. Joseph Monastery in Ava, Missouri.

To commission a gift for a priest or religious community, perhaps in honor of an ordination, profession, or anniversary, please contact Gwyneth.