The sun shall be turned into darkness, and the moon into blood: before the great and dreadful day of the Lord doth come.

—Joel 2:31

The Prophecy of Joel

After the descent of the Holy Ghost on Pentecost Sunday, when St. Peter preaches the Gospel for the first time, he explains that the prophecy of Joel has been fulfilled:

And it shall come to pass, in the last days, (saith the Lord,) I will pour out of my spirit upon all flesh: and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, and your young men shall see visions, and your old men shall dream dreams. And upon my servants indeed, and upon my handmaids will I pour out in those days of my spirit, and they shall prophesy. And I will shew wonders in the heaven above, and signs on the earth beneath: blood and fire, and vapour of smoke. The sun shall be turned into darkness, and the moon into blood, before the great and manifest day of the Lord come.

—Acts 2:17-20, quoting Joel 2:28-31

The darkness of the sun was realized literally during the conclusion of Christ’s passion, when “from the sixth hour there was darkness over the whole earth, until the ninth hour” (Mt 27:45, cf. Mk 15:33 and Lk 23:44). The sun is also a figure of the Son, “the light of the world” (Jn 8:12), so that Joel’s prophesy of the darkness of the sun also foretells the entirety of Christ’s passion, death, and burial, when His glory “as of the sun” (Mt 17:2) is concealed and darkness appears to have extinguished the light.

The moon is a figure of Our Lady, the “woman clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars” (Apoc 12:1). Just as the moon has no light of its own, but reflects the light of the sun, Our Lady “is the brightness of eternal light, and the unspotted mirror of God’s majesty, and the image of his goodness” (Wis 7:26). In the passion and death of her Son, Mary is the moon reflecting the Precious Blood.

A pietà, then—an image of the Sorrowful Mother holding her dead Son—is a representation of Joel’s prophecy of the sun “turned into darkness, and the moon into blood.”

Conceiving a New Pietà

When sacred artist Gwyneth Thompson-Briggs was commissioned to paint a pietà with Saints John and Mary Magdalen this Lent, she began, as she usually does, by turning to Scripture and the Old Masters. One of the first details to strike her as she read re-read the Passion narratives was the darkness that covered the earth while Christ hung from the Cross. “I kept imagining that darkness in relation to the Midwestern thunder storms we were having, and in relation to the solar eclipse I witnessed a couple of years ago,” Gwyneth recalls.

The timing of the darkness also struck the artist: “All three synoptic Gospels mention that the darkness lasted from the sixth to the ninth hour, roughly from noon to three, the three hours that Christ hung on the Cross. So by the time Our Lord’s body was laid in His mother’s arms, the darkness was probably at least lifting.”

Most artists, however, depict this moment against a darkened landscape. “Overwhelmingly, the Counter-Reformation masters—who are very attentive to Scripture and Tradition—set their pietà in profound darkness,” Gwyneth explains. “This is true not only of tenebrists—who regularly employed exaggeratedly dark shadows for visual and emotional effect—but also of artists like Titian, who are known for their use of color.”

She came to the conclusion that the artists were making a theological rather than a historical choice. They were representing the spiritual reality of the eclipse of the light of the world prophesied by Joel, recalled by St. Peter, and manifested in the Tenebrae service. “At this moment, the darkness appears to have comprehended the light. Darkness is certainly the affective experience for Our Lady, St. John, and the Magdalen. In the Counter-Reformation tradition, I wanted to convey the weight of their grief through the darkness of the landscape and the painting as a whole.”

The two works that most influenced Gwyneth’s conception were the 1633 Pietà by Giuseppe Ribera (1591-1652) that now hangs in the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid and the Avignon Pietà by Enguerrand Quarton (c.1410-c.1466) that hangs in the Louvre.

Ribera, a Spaniard working in Spanish Naples, was a tenebrist. The mourners in his Pietà seem ready to fade into the shadows; only their faces and hands catch the light. However, the entire body of Christ and much of His shroud are illuminated, from above. They occupy most of the bottom third of the painting, while the shadows occupy the top two thirds and form a thin strip on the bottom as well. One of the effects is to convey that the body of the dead Christ is still hypostatically united to His Divinity, even as it is surrounded by death, darkness, and grief.

Gwyneth explains: “Christ has died, but His human soul and His dead body remain united to the Godhead. The darkness appears to have comprehended the light, but it hasn’t. Ribera uses light and shadow to demonstrate the Church’s faith. And the Church in this moment is pretty much limited to these figures and the handful of others who stood by Christ to the end.” Thus Ribera portrays each of the mourners giving expression not just to grief but to faith. The Magdalen kisses the feet she has anointed and washed with her hair. Kissing feet is a sign of utter humiliation before God and before men who represent God. (Thus the immemorial custom of kissing the papal slippers.) To this day Christians will imitate the Magdalen when they venerate the Cross on Good Friday. Ribera is surely alluding to this liturgical practice, which usually entails kissing the wounds on the feet of the Corpus. St. John places his hand on Christ’s shoulder and holds the Sacred Head near his apostolic heart, a reversal of St. John’s repose upon the Sacred Heart during the Last Supper. Our Lady grasps her hands and raises her eyes in prayer; her immaculate faith lifts her heavenward even in the moment of her deepest dejection. “The serenity of Our Lady in the midst of her sorrows is a rich source for art. She never abandons herself to her grief; she retains her composure, her regality. That was something I wanted to convey in my painting Our Lady of Sorrows and also in this Pietà. Ribera is exemplary in depicting her regal grief, as is Quarton.”

Quarton’s Pietà departs from the tenebrism of Ribera. While the landscape in the foreground remains very low in value, he establishes a horizon line a little more than halfway up the picture, with some glowing buildings rising from it, set not against sky, but a plane of gold leaf. It is a Byzantine element in a work otherwise situated within the context and language of the Northern Renaissance. Like Ribera, Quarton seems to be contrasting the pit of lamentation with the sublime finality of the Resurrection—with an allusion to the heavenly Jerusalem on the horizon. Gwyneth was inspired by both Ribera and Quarton’s insertion of glory and hope side-by-side with sorrow. From Quarton, she also took the compositional arrangement of the figures around Christ’s body.

In addition to researching Scripture and art, Gwyneth revisited a book by 20th century French surgeon Pierre Barbet, A Doctor at Calvary. Barbet argues that rigor mortis would have set in before Christ was taken down from the Cross, something to which Quarton may allude. Gwyneth initially envisioned scrupulously depicting rigor mortis, but eventually decided only to suggest it.

The size of her work, 21 inches by 38 inches, was determined by the patron’s wall. “All through the process, I was trying to keep in mind that the painting was destined for a wall in a home,” says Gwyneth. It had to be a devotional work that would read well at close proximity. This demands a much more intimate approach—including tighter brushwork—than would be appropriate for a large altar-piece or painting destined for a high church wall.” For the surface, Gwyneth knew she wanted to work on linen, which is more finely toothed than cotton canvas and would facilitate the detail work. The linen also references Christ’s burial shroud, which Gwyneth knew she wanted to depict prominently within the painting.

While researching, Gwyneth sketched several concepts from imagination as part of the process of determining ways the scene could be rendered. After communicating further with the patron to understand his vision better, she sketched three more detailed possible compositions. For these she referenced figures from life, painting each figure for about ten minutes, to convey anatomy and basic lighting. The patron selected his favorite sketch and Gwyneth set to work.

Preparatory Work and Drawing

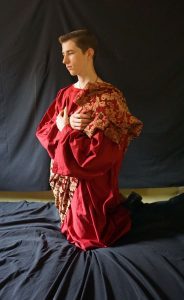

Before painting could begin, Gwyneth had to assemble a corps of models, collect drapery, sew costumes, prepare a raised platform, and adjust lighting in her studio. Then she would draw each figure.

Following the Baroque tradition, Gwyneth is convinced that depicting individual living persons as figures from sacred history is a mistake (see her comments in regards to Our Lady of Sorrows). Yet as a Western painter, and also to convey the reality of the Incarnation, Gwyneth is committed to painting from life, not purely from imagination. One solution is to reference multiple models for the same figure. For her Pietà, she began working with five primary models, one for each figure, plus an additional model for the head of Christ. She then used secondary models in the later stages, and some models sat for multiple figures. In total Gwyneth referenced ten models.

After her research in art history, Gwyneth decided to follow the tradition of depicting the figures in the primary colors, plus white for Christ’s loin cloth and shroud. Mary, of course, is associated with blue, St. John with red, and Mary Magdalen with yellow. Gwyneth suspects that the use of the primary colors is effective because it conveys the primal emotion of the scene. She selected the fabric and designed the costumes, then worked with a talented seamstress to quickly sew them.

Constructing a platform was necessary so that Gwyneth could see and depict the figures and drapery from eye level or slightly above. “The vantage point is very important for establishing a mood, and I felt the loftiness of the figures and scene would best be depicted from slightly below. I need to stand when I paint so that I can move around and especially so that I can move back and check my work against the figures. That necessitated building a raised platform.”

She lit the scene primarily from one strong source of natural light above and to the left of the figures. “A single source allows for the greatest distinction between lights and shadows,” she explains. “In order to convey the pervasive gloom, I needed to make the shadows fall on the figures themselves, not just behind them.”

With everything in place, Gwyneth began by sketching each model individually for three hours to create finished drawings of each figure, as well as the head of Christ. She then turned to a very untraditional source to unite the five drawings into a composite: her computer. “Had I lived in the Renaissance, my apprentices would have scaled each drawing and combined them into the composite. The computer is the closest thing I have to an apprentice.”

This image was submitted to the patron, who asked for an adjustment to the position of Christ’s head. Then Gwyneth could finally turn to painting.

Painting from Life, Art, and Imagination

Having coated the linen with PVA size, Gwyneth stretched it and applied an oil ground. Then she transferred the composite drawing to the canvas by applying charcoal to the back of the drawing and tracing the lines of the drawing with a stylus. She then painted over the transferred charcoal lines with oil paint thinned with mineral spirits.

Since she needed to eliminate all the white of the linen in order to depict the right hierarchy of values, reserving the highest value for the shroud, she blocked in basic color fields across the entire canvas. Then she began a rotation of painting from each model individually while working on the background between sessions with models. “In some respects,” she says, “it would be easiest to have all models present at all times, but that is unrealistic. Instead, I worked from one or occasionally two models at a time—as many Old Masters did. Working from each model on rotation allowed the entire painting to develop at the same time, lending unity to the painting. Every decision about one figure informed decisions about the others.”

One of the challenges of this method was keeping the figures proportionate to one another. Gwyneth found herself constantly readjusting the sizing of the figures. She also became more attentive to how disproportionate figures can be even in Old Master paintings. “The more you paint in their tradition, the more you admire them, even as you notice their mistakes and flaws. Sometimes the disproportion actually works pictorially, whether or not it is intentional.”

Initially, she had intended to spend more time with the model for Christ in the lap of the model for Mary. “I discovered very early on how awkward it is for a grown man to be limp in a small woman’s lap. It was not only uncomfortable for the models; it also looked very inelegant. In order to communicate the supernatural poignancy of the moment, it was necessary to bend the laws of physics” and prop up the models for Christ on furniture.

In addition to working from different models, Gwyneth developed each figure from memory and imagination between sittings. “After staring at the light hitting a model for several hours, you start to remember where the planes fall, and you can then paint without the model. This allows you to depict the sacred figure rather than merely the model or models.

Between sessions with the models, Gwyneth worked on the shroud and sky. “I was surprised by the difference between the color of the shroud in shadow—where it was turquoise and purple—and in the sunlight—where it was creamy, almost golden.” She sought to relate the colors of the shroud and clothing to the tormented sky and clouds. “Treating clouds seriously was one of the big firsts for me on this painting,” she says. “I realized the expressive possibility of clouds much more than I had before.”

For the most part, Gwyneth was inspired by clouds from Baroque paintings, especially a 1742 painting in the St. Louis Art Museum by Corrado Giaquinto that served as a proposal for the ceiling of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme. She did not paint directly from any artwork, however, and likens her approach to that of Millais. “Millais would meditate on scenes from life during the day, but he wouldn’t paint directly from life. Instead, he’d paint from memory back at his studio. You can’t capture the fugitive iterations of the weather—especially of stormy weather—on location. Instead, you have to pay close attention in life and then rely on your memory. Much of what I was doing was painting in light of my impressions from nature and from the Giaquinto sketch.”

Corrado Giaquinto, St. Helena and the Emperor Constantine Presented to the Holy Trinity by the Virgin Mary, 1742. St. Louis Art Museum.

Despite alternating between figures, drapery, and background, Gwyneth felt that the painting lacked unity. She decided to merge the shadows together by scumbling. “To scumble is a dry brush technique, where you apply a veil of paint over an area that has already dried. You can achieve various effects—the Impressionists scumbled to portray water lapping or the variegated surface of haystacks. I applied a neutral brown over the shadows to bring all the shadows closer together in value. In the lights, there is a great variety of color, value, and stroke. But in the shadows, I muted the differences, reducing the contrast between shadows.” Gwyneth also used a favorite technique of Da Vinci—sfumato, or the blurring of lines—to further reduce the visual information in the shadows and lend them greater unity. “That was the aha moment! With the shadows brought into greater unity, I saw the painting coalesce.”

In the lights, however, Gwyneth sought to incorporate not only tonal variety, but also to exploit variety of brushwork: “On the faces and hands, and even more so on the wounds, I employed very tight brushwork, while on the fabric, the brushwork is looser, with impasto. I wanted the trail of the brush to bring out the rhythm of patterns like the folds on the robes of the Magdalen and St. John.” She calls the employment of the full range of modeling “the dynamics of finish.”

The final steps of painting were getting the faces and hands exactly right. She repainted each face a dozen or more times. The trouble, Gwyneth says, is that capturing just the right expression is particularly elusive: “You have to let the paint swim around a bit until it comes into view. One stroke and the eyes close, another and they open, or the lips pucker, or smile or frown. When it is just right you want to cry out, ‘hold it, stop right there!’ And you have to let go or you’ll ruin it. It’s a bit like adjusting the syntax in a sentence, except that you can’t adjust it back.” She repainted each face a dozen or more times. “This painting required a lot of physical courage, especially to wipe out the faces,” she recalls. “I’d be in denial about a face being disproportionately small or large because I liked it. In particular, there was an earlier face for St. John which I thought was really fine. I had to keep in mind some advice from the writer and English professor, Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch: ‘Murder your darlings.’”

When she was satisfied, she submitted photos to the patron, who requested a few adjustments, including a veil for Mary Magdalen. “I’m actually really happy with how the veil turned out,” says Gwyneth. “There’s this Romantic idea out there that the patron always spoils everything and that if only the artist were completely free, his work would be a masterpiece. Well, we’ve had about a hundred years of total liberty for artists, and there hasn’t been a masterpiece since. In fact, I think that responding to the restraints imposed by patrons—like the restraints of architecture, physics, and morality—very often improves the artwork.”

Meditating on the Figures

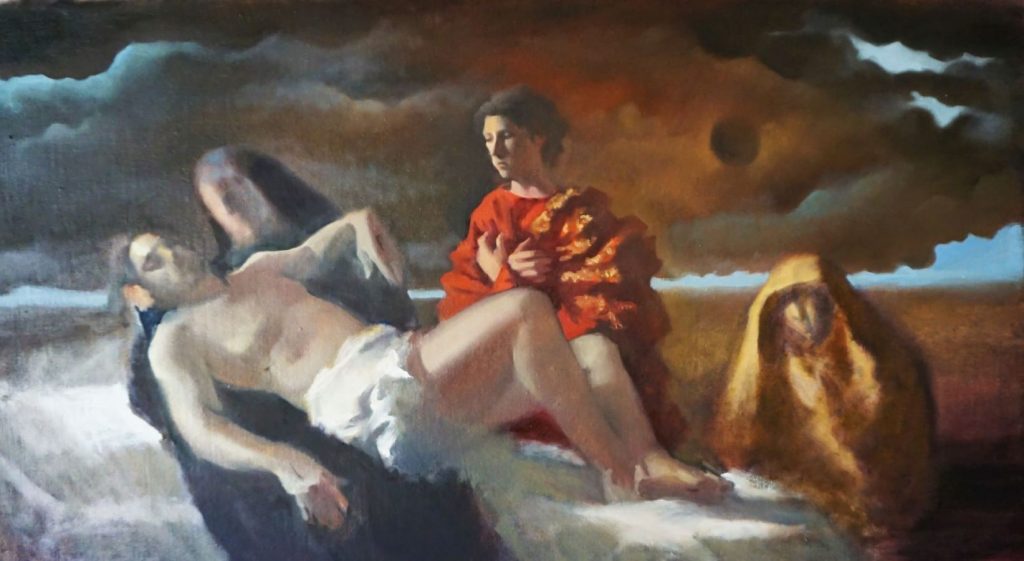

The overwhelming focus of Gwyneth’s Pietà is the body of Christ. Its size, nudity, and muscularity arrest the viewer, as well as its greenish tint. Gwyneth looked especially to the High Renaissance and Mannerist tradition in depicting Christ’s form. “It’s slightly elongated, and the scale is intentionally just a little disproportionate,” she explains. Hierarchic scale, where figure size is adjusted to convey importance, is rare in the tradition of Western naturalism, though it was common through the 14th century. Gwyneth’s exaggeration is slight, but enough to convey the overwhelming centrality of this dead body for the three mourners and for the whole world.

“The challenge of depicting the dead Christ is to show the reality of death as well as the reality of the continued union of His flesh with the Godhead.” “I am a worm, and no man,” says Psalm 21:7 of Christ, who will speak the Psalm’s first words among His last, “O God my God . . . why hast thou forsaken me?” In death, the separation of soul and body, Christ’s body is no longer integrated into a human being; it is only a corpse, food for worms. And yet, the Godhead is united to this mere flesh, and through the power of the Godhead united to this flesh and to Christ’s human soul, Christ’s soul and body will reunite and He will rise again triumphant over death.

Gwyneth attempted to convey this mystery by using different approaches to color and line. Color, traditionally associated with flesh, conveys His death: “The greenish undertones in the skin contrast with the warmer flesh tones of the living mourners.” Line is traditionally associated with soul, probably because line, like the soul, gives form to a body. Thus the size and idealization of Christ’s body convey His divinity, and point to the reunification of soul with body operated by the divinity.

In treating the wounds, Gwyneth decided to depart from the historical reality attested by the Shroud of Turin, mystics, and doctor Pierre Barbet, that Christ’s body would have been covered in blood and lacerations. “I love the Spanish tradition that emphasizes the bloody reality of the Passion, and I’d love to work in it someday,” she says, “but I had conceived this work as a more restrained meditation on the individual wounds. I guess you could say the painting is more Italian than Spanish.”

For the face of Christ, Gwyneth wanted above all to express Christ’s nobility in death. The angle of the face in the light allowed her to accentuate the brow, “a plane particularly expressive of refinement.” The angle also allows light to fall on the lids of the eyes, showing that they are closed.

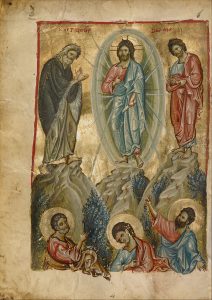

Surrounding the Sacred Body, says Gwyneth, “is a mandorla of mourners and shroud.” The mandorla is the almond-shaped aureole that surrounds Christ and sometimes the Virgin in Christian art from the Byzantine through early Renaissance periods. Usually the mandorla is used when depicting the Transfiguration, the Resurrection, Christ in Majesty, or some other scene where divinity or glory is manifest.

The Pietà’s allusion to this device is surprising in two respects. First, the Western tradition of painting largely abandoned the mandorla with the High Renaissance. Gwyneth’s work, including the Pietà, is firmly rooted in the Renaissance and Baroque tradition. Second, the device does not seem to have been used for depictions of the passion and burial, when Christ’s glory is least visible.

Gwyneth’s suggestion of the mandorla communicates the hypostatic union of the Sacred Body with the Godhead. This of course points to the Resurrection, which is further underlined by the use of the shroud to form part of the mandorla. The shroud of course will be the first material witness to the Resurrection, and because of the impressions left on it by this event, it continues to be a witness to the Resurrection, the ultimate proof of Christ’s divinity. Thus Gwyneth starkly contrasts the brightness of the shroud with the darkness of the ground. “Visually, I conceived of the shroud as a wave crashing on the shore,” says Gwyneth. She patterned the asymmetrical rhythm of the edge of the shroud on the edge of a wave. The shroud, then, points at once to the Resurrection and to the waters of Baptism.

The use of mourners to suggest the other half of the mandorla points to their role as the remnant of the Church in this moment. In a manner analogous to Ribera’s Pietà, Gwyneth shows the continued faith of Mary, John, and the Magdalen, in Christ’s glory, even at this moment when it is most eclipsed.

Placing Our Lady’s face next to her Son’s strengthens the allusion to the Madonna and Child type that is always present to some degree in a pietà. But the placement is even more suggestive of the prophecy of Joel, where the sun is darkened and the moon bloody. Christ, the light of the world, seems to be extinguished, but His Blessed Mother still reflects the blood of His passion; indeed, according to His humanity, the same blood courses through her veins.

To show Mary’s unique participation in Christ’s Passion, she is the only figure to sit atop the shroud: “The rhythm of white shroud, dark blue mantle, white shroud is a strategy to draw attention to Christ’s body, but it also literally inserts Mary into the mystery of the shroud. It is as if she too is about to be buried with her Son.” Our Lady, too, according to Tradition, will also be the first human witness of the Resurrection.

St. John is depicted toward the top center of the group, mourning the wound in Christ’s hand. Gwyneth sees this as an allusion to the priesthood: “John had been ordained the night before; his hands have been anointed to perpetuate the Sacrifice of Calvary in his lifetime and, through the apostolic succession which will also be communicated through his hands, until the end of time.”

In continuity with tradition, the Magdalen is the image of the penitent, attesting Christ’s power to forgive sins and pay their wages. She looks to the feet she has washed with her tears, spikenard, and hair, pointing to their wounds and to herself. Gwyneth explains: “She understands that He died for her sins; she reproaches herself for His death, as we must reproach ourselves.” And her veil, constraining her wild hair, is a type of the “wedding garment” from the parable of the Wedding Feast (Mt 22:12). St. Augustine interprets as a symbol of charity (Sermon 45 on the New Testament), the typical virtue of the Magdalen, given the words of Our Lord, “Many sins are forgiven her, because she hath loved much” (Lk 7:47).

Darkness, Blood—and Dawn

Gwyneth sought to convey the darkness that covered the earth and the blood of Christ reflected in the living body of His Mother, but also the light that was hidden but not extinguished on the Cross, and that would radiate anew on Easter morning. In the Paschal light, after the Ascension, the Holy Ghost would descend on the disciples—“upon my servants and handmaids in those days I will pour forth my spirit,” as Joel prophesied (2:29), probably with particular reference to Our Lady, “the handmaid of the Lord,” who would receive the Holy Ghost alongside John and the other disciples, surely including the Magdalen.

In Gwyneth’s Pietà the horizon line points to the light of the glorious Day of the Lord that will break forth on Easter and culminate in the descent of the light of the Holy Ghost into the hearts of the faithful on Pentecost. The flatness of the horizon contrasts with the dynamism of the turbulence of the clouds above and the drapery below. “In the colors and the movement of the clouds and clothes, I wanted to express the unity in grief of the mourners and the cosmos.” Yet, the painting also pierces this grief with the bright, assured line of the horizon, where, in accordance with Gospel accounts, light is already breaking through. “Much of what I was painting was the emotional feeling of light breaking through after a heavy thunderstorm,” she says.

The horizon line breaks with the “claustrophobic closing in of darkness” in Ribera, functioning somewhat like the gold leaf background in Quarton. “The suggestion of the gleam of light opens up the pictorial space. You can see off into the background for hundred of miles, as from a mount.” This at once anchors the scene on Mount Calvary and alludes to all the other mountains of sacred history where God reveals himself: Sinai, Carmel, Thabor. The spatial vastness thus opened up also suggests the temporal extension of the moment—the insertion of kairos into chronos. The grief of the moment extends throughout time, uniting us to the grief of Our Lady, St. John, and St. Mary Magdalen. Yet at the same time we see the grief transfigured, because the darkness has not comprehended the light.

Looking Forward

Gwyneth painted the Pietà during Passiontide and Eastertide, timing she considers providential. “It was a special grace to work on this painting during the holiest season of the year. I saw the passion of Our Lord and the compassion of Our Lady, St. John, and Mary Magdalen, not only in the bleakness of Holy Week, but also in the light of Easter. The Paschal light does not obliterate the suffering, like waking from a nightmare; rather, it reveals the glory of suffering.”

Practically, Gwyneth is also grateful to the patron for the chance to work on a multi-figure painting. She says she could never have done the painting without a commission. “Finishing this one painting involved ten models, sewing costumes, staging—a lot more than linen and paint! The importance of patrons cannot be underestimated, especially for sacred art. It’s like the line at the end of Isak Dinesen’s ‘Babette’s Feast’: ‘through all the world, there goes one long cry from the heart of the artist: Give me leave to do my utmost!’”

The result of the patronage of this Pietà is not just the painting, but the employment and engagement of ten models, including two young people interested in pursuing art, and an increase in skill and knowledge on the part of the artist. Gwyneth feels more prepared than ever for her next project, especially for her next multi-figure commission: “I understand how to incorporate multiple figures much better now. Every time I do a painting,” she says, “I feel inspired to do the next one even better.”