“They have poured out the blood of the saints as water, round about Jerusalem, and there was none to bury them.”

—From the Tract for the Feast of the Holy Innocents (Psalm 78,3)

“The blood of the saints is the seed of the Church.”

—Tertullian, Apologeticus 50

On the fourth day of Christmas, December 28, the Church traditionally donned violet vestments to mourn the slaughter of the Holy Innocents—“the male children that were in Bethlehem and in all the borders thereof, from two years old and under”—by Herod the Great (Mt 2:16). Until 1961, the vestment were violet, not red, the color of martyrs, though the Innocents have always been honored as martyrs.* They are martyrs indeed, for they lost their lives for Christ’s sake (see Mt 16:25), but they are unique among martyrs in that they confessed Christ “not in speech, but by death” alone (Collect), and this some thirty-three years before Christ’s death. The Innocents died in His stead, in anticipation of the substitution Christ would make on the Cross for their original sin and for the sins original and actual of all mankind. Thus, perhaps more than other martyrs, the Innocents’ martyrdom is hidden within Christ’s Passion, which we commemorate traditionally with violet, not with red, throughout Passiontide.

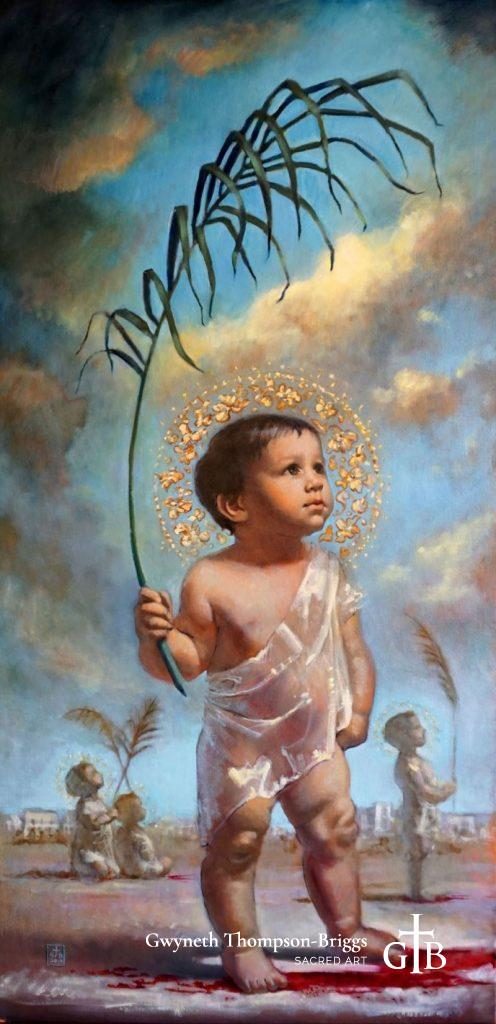

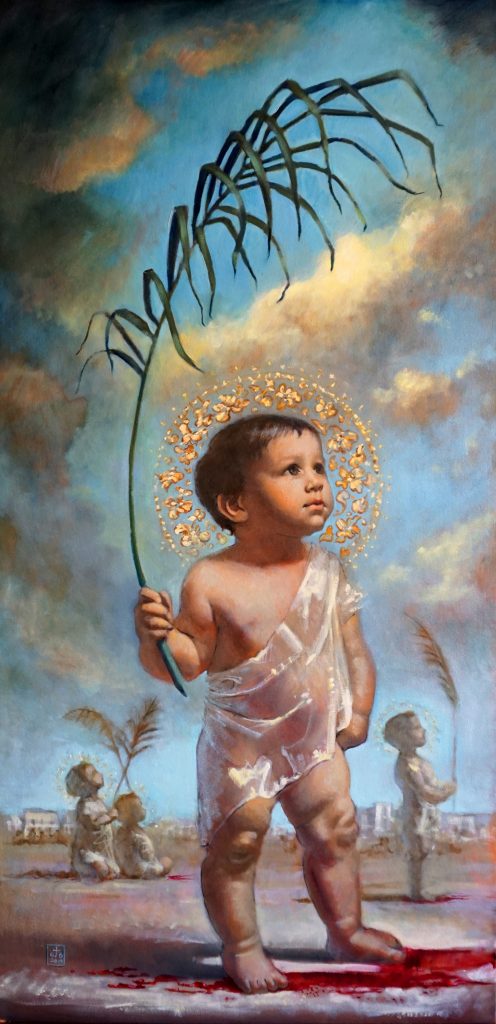

There is no violet in sacred artist Gwyneth Thompson-Briggs’s new painting, The Holy Innocents, but the image is a meditation on the hiddenness of their martyrdom. She conceived the work as an aid to the pro-life cause, because the slaughter of the unborn is likewise hidden from view.

Abortion is by far the leading cause of death worldwide. The pro-abortion World Health Organization estimates that there are 56 million abortions worldwide each year. That comes to 153,000 per day and 107 per minute. In reality the number is much higher, because these figures exclude abortions caused by so-called contraceptives. “It’s easy to feel hopeless when you think about statistics like these. We can’t end the slaughter by natural means alone; we need supernatural help,” says Gwyneth. “There are many great patron saints for the pro-life cause, among them Our Lady of Guadalupe, St. Michael the Archangel, the 3rd century mothers and martyrs Saints Perpetua and Felicity, the 18th century lay brother St. Gerard Majella, and the 20th century mother and pediatrician St. Gianna Molla.”

What attracted Gwyneth to the Holy Innocents in particular was their proximity in age and experience to the unborn. She hopes her painting will help draw attention to the humanity of unborn children and encourage viewers to seek the intercession of the Holy Innocents to end abortion. “It seems to me that part of why abortion is so commonplace is that it is largely invisible,” she says. “You can’t see the unborn. I wanted this painting to bring to mind the child in the womb and make real the horror of their young flesh being destroyed. I knew the flesh would have to be very real and beautiful.”

Depicting the Dignity of Babies

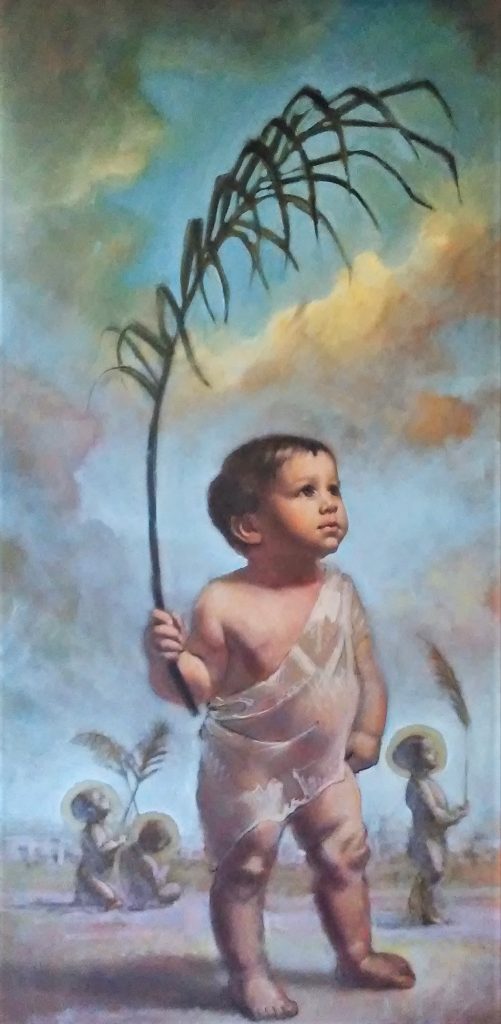

Against a turbulent sky, four Innocents wave palm branches, the symbol of the martyr’s victory over death adapted from the military triumphs of antiquity. Their gaze is turned aloft, in contemplation of the beatific vision, while the earth—with Bethlehem on the horizon—is stained with their blood. Nimbi inset with golden flowers crown their heads, a reference to the hymn, Salvete flores martyrum—“Hail, Flowers of the Martyrs,” sung on their feast. Besides the blood, there is no reference to violence; this is not a painting of the Slaughter of the Innocents, a widespread subject in Western art. The mood is quiet, reflective, mysterious; in the history of art it perhaps most closely resembles The Triumph of the Innocents, by the Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt.

“It’s a devotional image, not illustrative, and that’s unusual for the Holy Innocents,” says Gwyneth. “Their slaughter is so horrific, artists and patrons seem compelled to depict it. Even Holman Hunt’s very distinct image is partly illustrative: it depicts the Innocents accompanying the Holy Family on the flight into Egypt.” Gwyneth notes the theological profundity of Hunt’s depiction, which illustrates how the Innocents help the Christ Child to escape by dying in His place. “It’s a wonderful painting, if sentimental. One certainly sees the Victorian cult of the child, which substitutes preciousness for dignity.”

Gwyneth fears that the modern obsession with babies as cute—and the broader kawaii craze—functions like lust. “The impure gaze reduces other human beings to flesh for consumption. Similarly, does the kawaii gaze reduce babies to objects of pleasurable consumption? Perhaps that is one reason why we see the coincidence of kawaii and abortion in modern post-industrial societies. When the meaning of all acts and persons is reduced to pleasure, the measure of all acts and persons is the pleasure they give.”

One of Gwyneth’s challenges, then, was how to depict babies with full natural human dignity—and also with the perfected dignity of the saints. She needed to depict babies worthy of veneration. There was no dearth of images to consult in the tradition of sacred art. “Earlier ages did not reduce babies to cute objects,” she says. “There are plenty of serious, stern, frowning, impassive, aloof, or otherwise dignified Christ Childs in the history of art.” One baby Jesus Gwyneth found inspiring was from an Adoration of the Magi by Spanish Baroque painter Fray Juan Bautista Maíno: “Christ is blessing the magi with a composed, distant expression—the liturgical blankness that suggests the beatific vision.” Gwyneth also found inspiration in Federico Barocci’s Circumcision, in Marianne Stokes’s Madonna and Child, and in her own children. “Every parent knows that babies can be very solemn,” she says. “There are moments when they seem to display a wisdom beyond their experience; I tried to crystallize those moments in this painting.”

Working with a Toddler Model

Gwyneth’s painting focuses on one Innocent who—she admits—is cute, “but hopefully more than cute.” The model was her one year-old daughter. “I’ve been meditating over this painting for years, but it seemed like the perfect subject for this point in my life because I painted it as the mother of a one-year-old and a two-year-old.”

Working with a one-year-old model posed unique challenges and opportunities.

Normally, Gwyneth works strictly from life, but since “it is impossible to have a one year-old pose for any amount of time,” she knew she would have to take photo references. To compensate for painting in part from reference photos, however, Gwyneth also drew the model from life in a number of quick sketches, using a technique she learned in two art classes: Drawing the Dancer and Animal Anatomy. “Both dancers and animals move frequently and unexpectedly, but they often reassume the same poses. One way to sketch them is to start a variety of poses as the model moves, and then to switch between the sketches as the model reassumes each pose.” Gwyneth used this technique when sketching her daughter.

Gwyneth also found several advantages in using a toddler model. “They have perfect posture,” she notes. “Also, they possess a vital tension. On the one hand, they can stand and move about, yet they are wobbly. Their legs are very sturdy, yet they lack agility. They are in perfect health and vigor, yet they are undeveloped—they are overflowing with potency becoming act. It’s very exciting to sketch.”

Gwyneth spent a couple of hours following her toddler around the studio “as she knocked things about.” “She had absolutely no interest in the toys I had brought her; she only wanted to play with the paints, solvents, and brushes.” After two hours of increasing frustration, Gwyneth gave up and turned to photography.

“She was very uncooperative, and she was dressed only in a diaphanous scarf, so the photoshoot was also cut short,” Gwyneth recalls. After sorting through the mostly unusable images, Gwyneth crafted a composite of photos to develop the pose for the painting. Alternate photos and sketches provided the basis for the smaller figures in the background.

Tradition and Innovation in the Painting Process

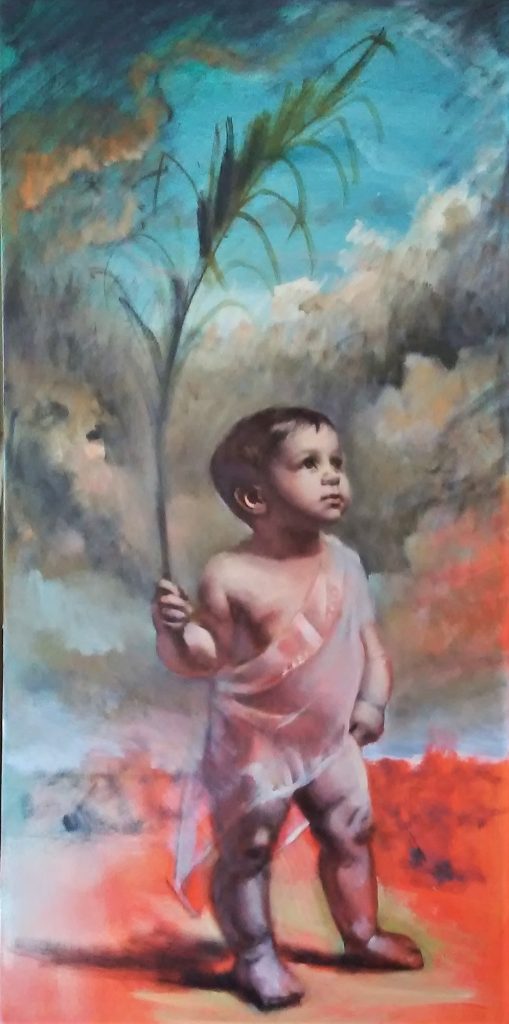

Traditionally, canvases are primed with a single color, usually dark, to provide tonal unity. Velázquez began by covering his canvas in burnt umber; others from a cool grey. For the Holy Innocents, Gwyneth elected to try a technical experiment.

“I started with a luminous tangerine fireball in the lower half, and a deep teal above,” says Gwyneth. “I felt it communicated the intensity of this spark of life within this sin-darkened world. I suppose an abstract artist might have left it at that. To some extent, this painting developed like the history of art in reverse—starting with abstract expressionism and ending in the Baroque.”

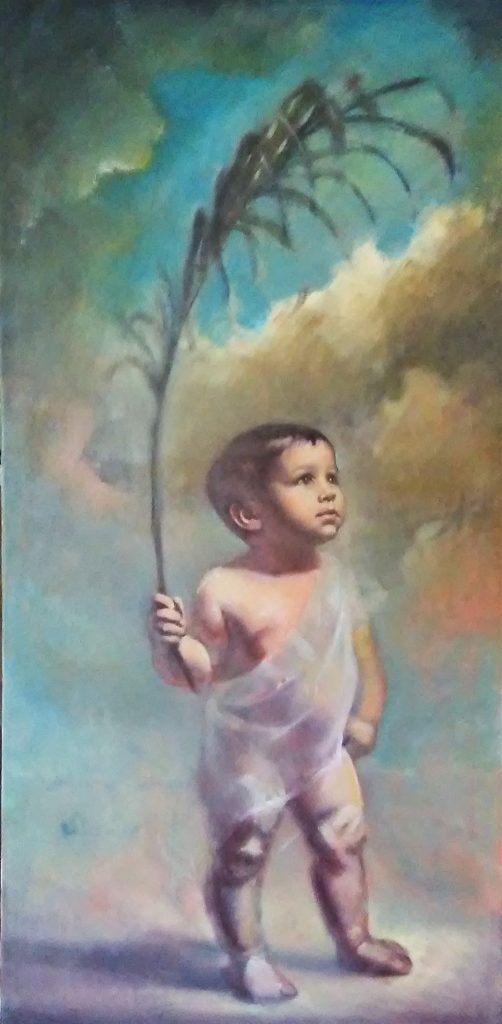

With canvas primed, Gwyneth sketched in the main figure, relying in part on a fresco technique she observed in works by Giambattista Tiepolo. “The technique is a departure from the Boston School in which I was trained; in some ways it transcends it,” she says. The painter does capture the light and shadow on a form as one observes it in nature, as in the portrait tradition coming down from Velázquez, but the painter also emphasizes certain shapes with very fluid, dark paint. In effect, the figures are outlined. “It is a technique particularly well-suited to large murals, like John Singer Sargent’s in the Boston Public Library and Museum of Fine Arts. I think it makes the figures easier to apprehend from a distance—or when reproduced quite small,” Gwyneth explains. “It also lends a vitality that a more naturalistic approach can lack.”

This was Gwyneth’s second recent painting, after her Pietà, to include clouds as an important feature. Again, she spent time gazing at clouds in nature and in art. “Clouds are really fun to paint because there are no strict rules for how a cloud is shaped,” she says. The lack of rules also makes clouds a challenge to depict convincingly. “As I painted, I kept making them too symmetrical, or too close to recognizable shapes. They needed a lot of adjustment to look organic,” Gwyneth recalls.

Gwyneth also had to be careful that the clouds did not overwhelm the figures. She wanted two principle foci—the face of the Innocent in the foreground, and his martyr’s palm. “I had to be careful that the clouds did not distract from the face and the palm, even as I used them to lead the eye around the canvas,” she explains. The clouds in the upper edges of the canvas are fairly dark and ominous, while the blue sky breaks through around the primary martyr’s palm.

The final step was encircling each martyr’s head with a nimbus. Originally, Gwyneth planned to use shell gold, which she had employed for the lettering in her painting St. John Fisher. Leafing through paintings by two masters from the Low Countries changed her mind. “Looking at Holbein and Rembrandt, I realized that they chose to depict rather than to use gold. It better approximates the experience of seeing gold in life,” Gwyneth says. She decided that shell gold would overwhelm the painting, diminishing the power of the hidden martyrs’ young flesh.

An Icon for the Unborn

Gwyneth does not know where the original painting will hang, but she does know she wants to license the image to pro-life groups. “I’d like to provide high resolution digital images for use by any pro-life group that thinks the image could be helpful,” she says. Knowing the painting was destined in part for digital reproduction was part of why Gwyneth painted such a large canvas—four feet tall by two feet across. It would be especially suited for hanging in a church, chapel, or large room, where it could be appreciated from some distance.

Wherever The Holy Innocents is viewed, Gwyneth hopes it manifests the dignity of babies born and unborn. “It is easy to oppose the murder of babies we can see and kiss and cuddle. Sadly, it is also easy to ignore the murder of babies we can’t see,” says Gwyneth. “With this painting, I’d like to contribute to making visible the slaughter of the innocents in our day. That’s why I had to include their blood ‘poured out like water’ around Bethlehem, where just a few days before the Christ Child was ‘wrapped in swaddling clothes and lying in a manger.’”

Essentially, then, The Holy Innocents is an icon of hope. The martyrs’ bodies bear no marks of their slaughter, they wave palms of victory over death, and their heads are crowned with everlasting glory. “Victory over abortion is possible because with God all things are possible,” says Gwyneth. “First, last, and always, we need to pray.” She hopes her painting encourages the invocation of the Holy Innocents to protect children from abortion: “The Holy Innocents triumphed over their slaughter in Herod’s world. They can help us triumph over the slaughter of the innocents in our world.”

Updates

Posters and chocolate bars bearing images of The Holy Innocents partook in the Walk for Life West Coast in San Francisco on January 25, 2020, through the generosity of the EWTN Media Missionary Program in the Diocese of Santa Rosa, California.

The Holy Innocents was exhibited at the 43rd Annual Respect Life Convention in St. Charles, Missouri, on October 13, 2019.

Holy cards are available in the shop.

*For more on the peculiarities of the traditional liturgy for the Holy Innocents, visit New Liturgical Movement.