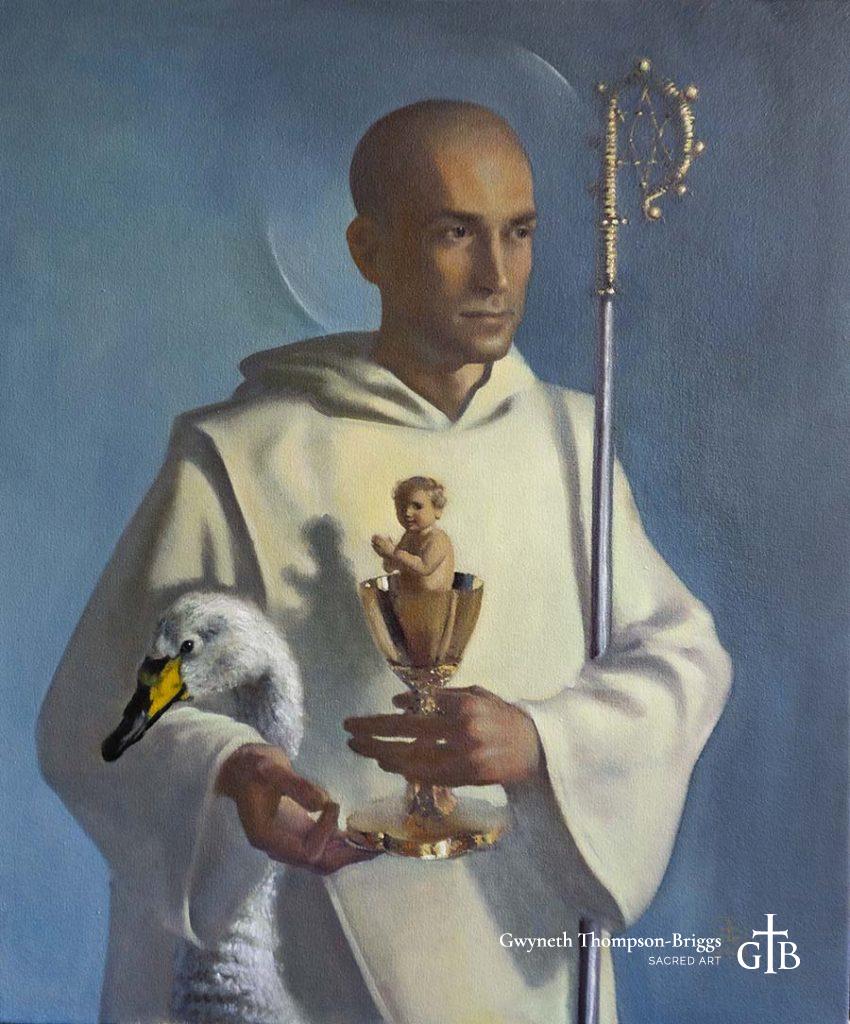

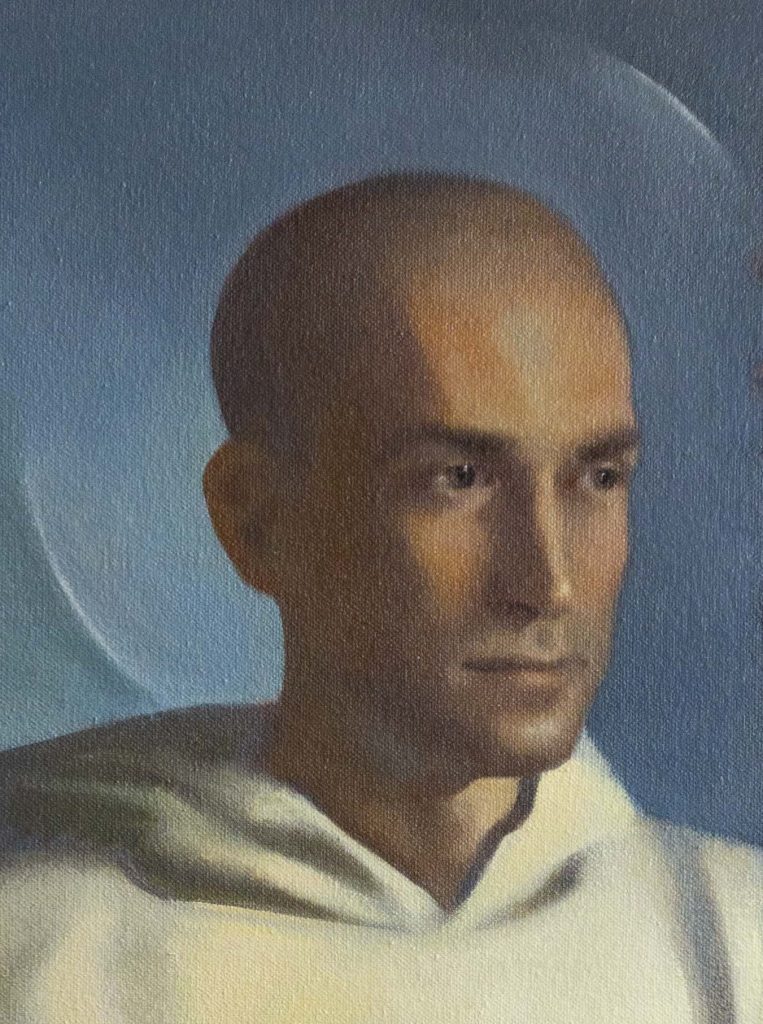

“If you blur your eyes or view the painting from afar, the emblems disappear; what remains is the figure of a man wearing white robes against a blue-grey background, standing in warm light.”

This is how sacred artist Gwyneth Thompson-Briggs sums up her new painting of St. Hugh of Lincoln, the 12th century Carthusian monk who was plucked from the obscurity of the Grande Chartreuse to become bishop of Lincoln and advisor to the Plantagenet kings Henry II and Richard Cœur de Lion. Gwyneth designed the painting to capture what she sees as the essence of St. Hugh.

“I think he was essentially a Carthusian monk who would have preferred to remain obscurely at prayer in the monastery, but a monk whose natural talents and fidelity to the divine will led him to the fruitful exercise of high spiritual and temporal authority,” Gwyneth says. In her reading, St. Hugh’s life might be divided into two phases or movements.

First there was the movement toward an ever more radical abandonment of the world to know only “Christ, and him crucified” (1 Cor 2:2). After living first in the world, then with his father among Augustinian canons regular, Hugh became a Benedictine novice at fifteen, rising to become prior of a monastery. Soon after, when Hugh was in his thirties, he discovered the Carthusian Order. Founded by St. Bruno in 1084 in a remote Alpine valley, the Order combines the eremitical and the cenobitical versions of monasticism. As a Carthusian choirmonk, Hugh would have lived out the Order’s motto—Stat crux dum volvitur orbis (the Cross stands steady while the world turns)—by singing Matins, Lauds, the conventual Mass, and Vespers in common, and spending the rest of the day alone in his cell praying the Office, meditating, studying, and tending a small garden.

After the renunciation of the world came Hugh’s progressive return into it: first as procurator at the Grande Chartreuse, the Order’s motherhouse, then as prior of a struggling new charterhouse in England that King Henry had founded in lieu of going on the crusade imposed as his penance for murdering St. Thomas of Canterbury, and finally, through Henry’s influence, as bishop of Lincoln. But like his Lord, Hugh returned from his forty days in the desert having vanquished the world, the flesh, and the devil, ready to supply others in their own battles for salvation. Amidst the noise of medieval politics, St. Hugh spoke the wisdom derived from a life lived in the perpetual silence of interior prayer.

An anecdote told by an anonymous 19th century Carthusian illustrates Hugh’s relationship to prayer and politics. One feast day when Hugh, Bishop of Lincoln, and another Hugh, Bishop of Coventry, were expected in audience with King Henry II, the brother bishops found themselves together in choir at a conventual Mass. The Bishop of Coventry omitted the solemn tones proper to the day, and began speaking the Introit. The saintly Bishop of Lincoln interrupted him, chanting the Introit from the beginning with the proper solemnity. When the Bishop of Coventry protested, “We must make haste, for the King will be waiting for us, and he is in a great hurry,” St. Hugh retorted: “I can’t help that; we must do homage first to the King of kings. No secular employment can dispense us from what we owe to Him; and our service today should be festive, not restive.” (Life of St. Hugh of Lincoln, page 235; see citation below.)

In order to worship God more perfectly, it was St. Hugh who began rebuilding Lincoln Cathedral in the new Gothic style after the earthquake of 1185. After his death in 1200, his tomb there became a center for English pilgrims drawn by the charity of a man whose love for God in the liturgy overflowed into rebuking kings and curing the tumors of children. Another King Henry, Tudor, destroyed the shrine, lest “the simple people be moch deceaved and broughte into greate supersticion and idolatrye.” The shrine’s gold, silver, and precious jewels were safely deposited in the royal treasury.

The Commission

When approached about painting St. Hugh, Gwyneth was unfamiliar with the saint. The patron, an American, was interested in commissioning an image for his home to foster his family’s personal devotion, but also to promote St. Hugh’s cult more broadly.

Gwyneth was immediately intrigued by the idea of painting another saintly English bishop after her 2018 painting, St. John Fisher. “The more I researched St. Hugh, the more I recognized the timeliness of his witness,” she explains. “The crisis in the episcopacy keeps worsening; we have so few models of good bishops. St. Hugh, like St. John Fisher, can help remind us all—but perhaps especially today’s bishops—what saintliness looks like in a bishop.” The life she found most helpful was published at the Grande Chartreuse in 1890 by an anonymous monk and translated into English by the Jesuit Herbert Thurston in 1898 under the title, The Life of Saint Hugh of Lincoln.

In addition to reading about St. Hugh, Gwyneth researched artistic depictions of St. Hugh. Usually depicted as a bishop, artists have given Hugh several attributes; among them a chalice with the Christ Child, based on a Eucharistic miracle; and a swan, based on well-attested accounts of a pet swan from Hugh’s episcopal estate at Stow. Gwyneth was particularly influenced by a 1632 canvas by Vincenzo Carducci depicting St. Hugh divested of his pontifical finery, wearing the simple robes of a Carthusian. From it she developed the idea of depicting Hugh in Carthusian robes but holding a bishop’s crosier. Before developing her design, she also studied several fine depictions of anonymous Carthusian monks, including the Portrait of a Carthusian by Petrus Christus and one by Moroni. “I conceived the painting after the manner of the paintings of anonymous Carthusians,” she says, “but with the attributes of St. Hugh the bishop and wonder-worker superimposed.”

Preparatory Drawings & Color Studies

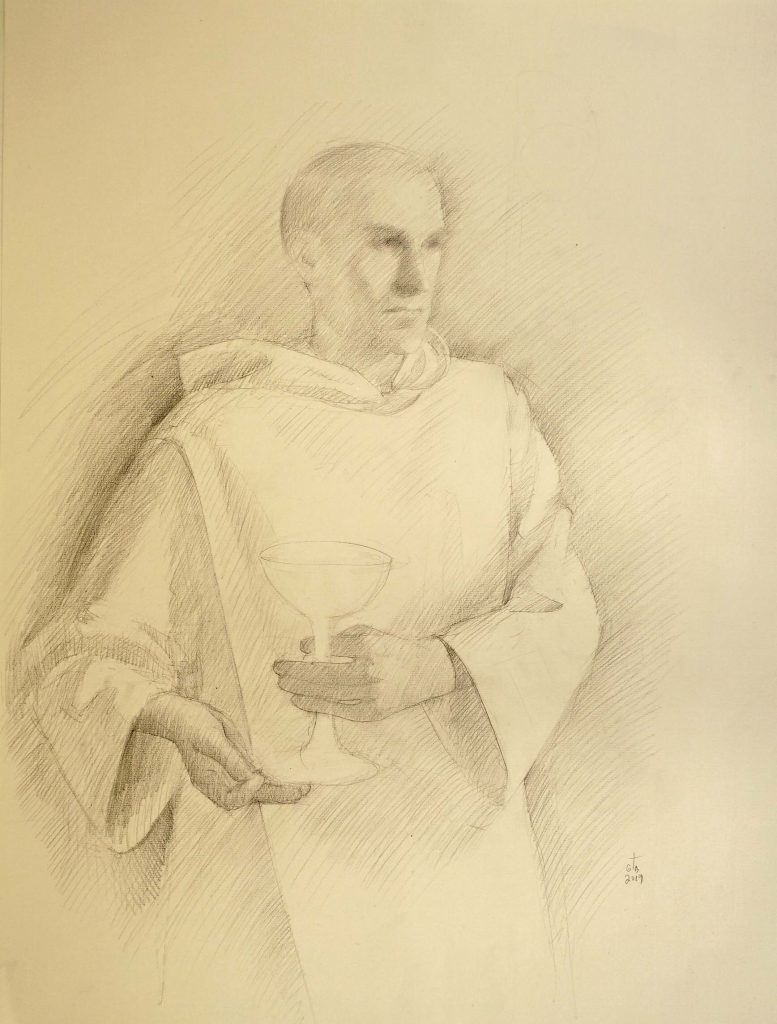

After Gwyneth and the patron had agreed on the design, Gwyneth set about collecting props and models. She decided against intruding on North America’s only charterhouse, in Vermont. Instead Gwyneth used artistic depictions to pictorially adapt a habit generously lent by the Dominican Priory in St. Louis.

As for her Holy Innocents, Gwyneth followed countless artists in making an asset of having small children in the house: “Anyone who’s seen a Rubens knows he had lots of children—baby fat abounds in his paintings, whether of cherubs or antique beauties.” For St. Hugh, Gwyneth found a model who looked at once austere, intelligent, and playful. Hugh was known for his wit, which more than once charmed a king incensed by the bishop’s probity. “Any man who kept a pet swan had to have a sense of play,” Gwyneth observes. She made sketches and color studies of both models, noting that “one of them was particularly skilled at holding the pose.”

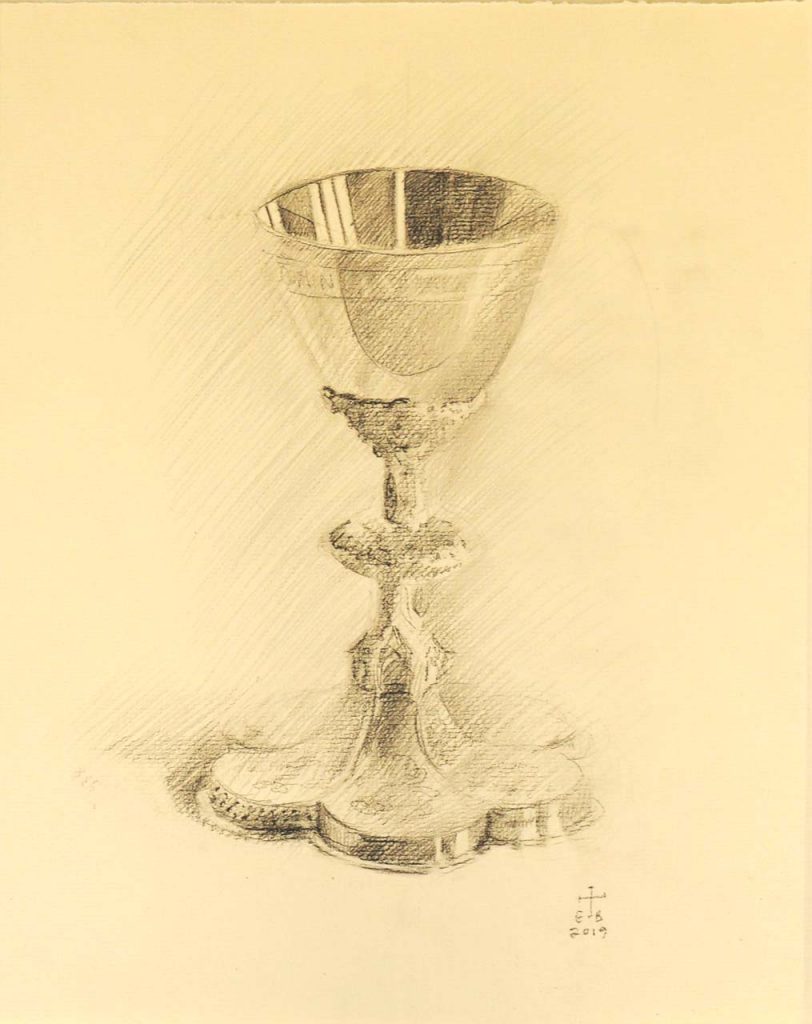

For the chalice and crosier, Gwyneth consulted images of Gothic crosiers and chalices (the Chalice of Abbot Suger is one of her perennial favorites), but elected to use simpler models. “I didn’t want the astounding beauty of the objects to distract from their roles in the painting,” she says. Ultimately she relied on the generosity of a local rector and sacristan, who allowed her to sketch and paint in the sacristy. The crosier was borrowed from the statue of another saintly bishop from the Alps, St. Francis de Sales, but the chalice was authentic. She chose a neo-Gothic chalice to match St. Hugh’s rebuilding of Lincoln Cathedral in what was then known as the “French” or “modern” style. Back in her studio, Gwyneth used a wineglass double with her model.

It was Hugh’s swan that proved most elusive. After overtures to the zoo proved fruitless and the price of taxidermized specimens from Russia proved prohibitive, Gwyneth connected with the Audubon Center in West Alton, Missouri. They invited Gwyneth to sketch from two stuffed trumpeter swans and to attend the annual trumpeter swan convention during the November migration season. Since Hugh’s swan was not a trumpeter but its Eurasian counterpart, the whooper swan, Gwyneth adapted a sketch from one of the Audubon specimens with photo references.

The preparatory drawings do not always depict the objects as they will appear in the finished painting. Rather, as Gwyneth sees the object better by drawing it, she discovers how to adjust the object’s position, shape, or value range. Gwyneth liked the sketch of the crosier, but realized that the angle was too distracting for the final composition. The chalice, on the other hand, was closely translated into the painting.

“Ideally, I’d have all the elements in the same place at the same time, but that’s often impractical or impossible. Perhaps there’s an analogy in filmmaking, where scenes are rarely shot in chronological sequence, but according to location or an actor’s schedule. One has to constantly remember how one scene relates to all the others,” Gwyneth says.

In translating an element from a drawing to a painting, something is lost and something is gained, she says. “There’s a freshness in the initial engagement with an object that is always lost through repetition. That’s one advantage to direct painting,” where the artist paints without preparatory drawings or underpainting. To suit the contemplative St. Hugh, Gwyneth chose to work in a more deliberate manner, contemplating each object and bringing them together incrementally on the canvas. Seeing an object over the course of time allows the artist to distinguish what abides from what changes, in continuity with the Carthusian motto. “Especially in observing the habit on the model over the course of several days, I began to see the dominant drape that underlies the constantly shifting folds,” Gwyneth says. “Similarly with the chalice, the slight movement of the hands and the passage of the light through the window lend a peripatetic sparkle, but long looking establishes the dominant glow.”

The Painting Process

Gwyneth chose cotton duck canvas to take advantage of the texture of the cotton, especially for the habit. After priming the canvas, she applied undercoats to set the overall value range—the pale gold of the habit against the blue background. She then tried to build up all areas of the painting simultaneously. “I worked in several rounds—a bit on the figure, then the chalice, the Christ Child, the swan, the crosier, then a bit more on the figure, the chalice, etc.” Through this process of progressive development, Gwyneth established unity, always one of her primary concerns.

“Unity in painting is partly the fruit of spatial and tonal composition, but no matter how unified the design, the artist always needs to adjust during the painting process,” Gwyneth says. “I find that if I let myself get carried away bringing one area too close to a finish, I wind up having to rework it—thus destroying the freshness of the finish—to unite it with the other passages.”

Attention to unity was especially important in this painting because of the variety of elements that might compete for attention. Gwyneth sought to establish unity partly by organizing the areas of focus along a diagonal from lower left to upper right—moving from the swan to the chalice with the Christ Child to the face of the saint and finally the crook of the crosier. Each element was designed to have a strong light/shadow pattern, establishing each as a focal point as well as bringing each into relation with the others. Gwyneth also sought to organize the focal points into a hierarchy of importance by varying the degree of contrast and finish and through placement along the diagonal. At the heart of the painting is the chalice, then the saint’s face, while the swan and crosier are closer to the margins and less fully developed.

Tonally, Gwyneth established unity by working with a limited spectrum of hues—from white to gold to silver to black—except in the background. Getting the color of the background right was one of the most challenging parts of St. Hugh, especially as the relationship between the background and the habited figure was the central idea Gwyneth wanted to convey. “The color of the habit dictated the color of the background, but finding exactly the right color took time. When the background was too light, the habit didn’t stand out, but when it was too dark, the shadows in the habit and the emblems didn’t stand out. When it was too blue, the chromatic intensity distracted from the figure, but when it was too grey the whole painting appeared drab. It was a long exercise in finding the perfect middle tone,” Gwyneth recalls.

A crisis arose toward the end of painting when Gwyneth realized she had to shift the angle of the crosier to make it less distracting. Unable to work from her preparatory drawing, Gwyneth was at the point of scheduling another visit to the sacristy when she remembered a battered old umbrella stroller in the basement with an appropriately hooked handle. She covered it with aluminum foil to reflect the light and set it up in her studio. “There wasn’t a lot of usable visual information, but that might have actually helped me to subordinate the crosier in the hierarchy of focal points,” she says. The patron had requested some allusion to St. Hugh’s protection of the Jews of Lincoln from persecution by King Richard, so Gwyneth inserted a star of David in the center of the crook.

The last strokes were those of the subtle nimbus. Gwyneth sought to represent St. Hugh’s holiness spherically, “like heat waves radiating from the fire of charity within him.” She particularly wanted to avoid the “plate model” of halo found, for instance, in Masaccio’s frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel. “Unlike the two-dimensional haloes that persisted in much Trecento art even after the development of spatial extension, Masaccio’s haloes exist in three-dimensional space, but they have always struck me as distractingly close to state dinner plates,” Gwyneth explains. “I wanted to show the atmosphere around the saint distorted by his holiness.”

One often overlooked element in painting is the selection of the frame. When possible, Gwyneth likes to select a frame before she begins painting, just as she selects models, fabrics, and props. “The frame is at once an extension of the painting and its primary mediator into an architectural setting; it’s very important to select a frame that supports and does not overwhelm a painting. Some paintings are suffocated by their frames, like a Victorian debutante corseted into a satin ballgown.” For St. Hugh, Gwyneth selected a wide gold frame with a little masculine detail, at once suggestive of saintly glory and Charthusian austerity. “Gold is almost always best for a saint,” says Gwyneth, who admits to regret that she was never an Indian bride.

A Saint and his Swan

St. Hugh’s swan appeared at the episcopal manor of Stow on the day of his enthronement as bishop. It did not resist capture by the people of the manor, who offered it to Hugh on his first visit. Immediately, the swan ate from Hugh’s hand and became attached to him. “It was sometimes seen to bury its head and its long neck in the wide sleeves which St. Hugh wore, as though it were plunging them in limpid water, giving utterance all the time to cries of joy,” recounts Hugh’s biographer. It slept in his chamber, was his constant companion during every visit to Stow, and even prophesied his death.

After Hugh’s death a poet compared Hugh to his swan: “The Saint, in life as pure as thy white breast / In death as fearless, lulled with a song to rest.” Hugh’s biographer agreed: “No other inscription or device could so well express the sanctity and purity of the Saint in his labours on earth and the serenity of his death, as this graceful and realistic symbol, taken in this case not from a mere legend, but from authentic history.” (Life of St. Hugh, pages 141-147.)

Gwyneth depicted the swan nestling into the crook of Hugh’s arm, in continuity with the eyewitness account quoted above and in parallel with the bishop’s crook in the upper right of the painting.

To contrast the softness of the swan’s feathers with the smooth shininess of his eye and beak, Gwyneth used disparate techniques. For the feathers, she applied very little paint to the end of her brush’s bristles. When applied, this leaves many thin, broken streaks of color on the canvas, approximating the appearance of fur. For the harder surfaces, she used a wetter brush, adding linseed oil to the paint. “Out of the tube, the paint has the consistency of toothpaste. For clean, smooth lines—appropriate for depicting hard, smooth surfaces, you mix the paint with a thinner of oil or turpentine until it resembles heavy cream,” Gwyneth explains.

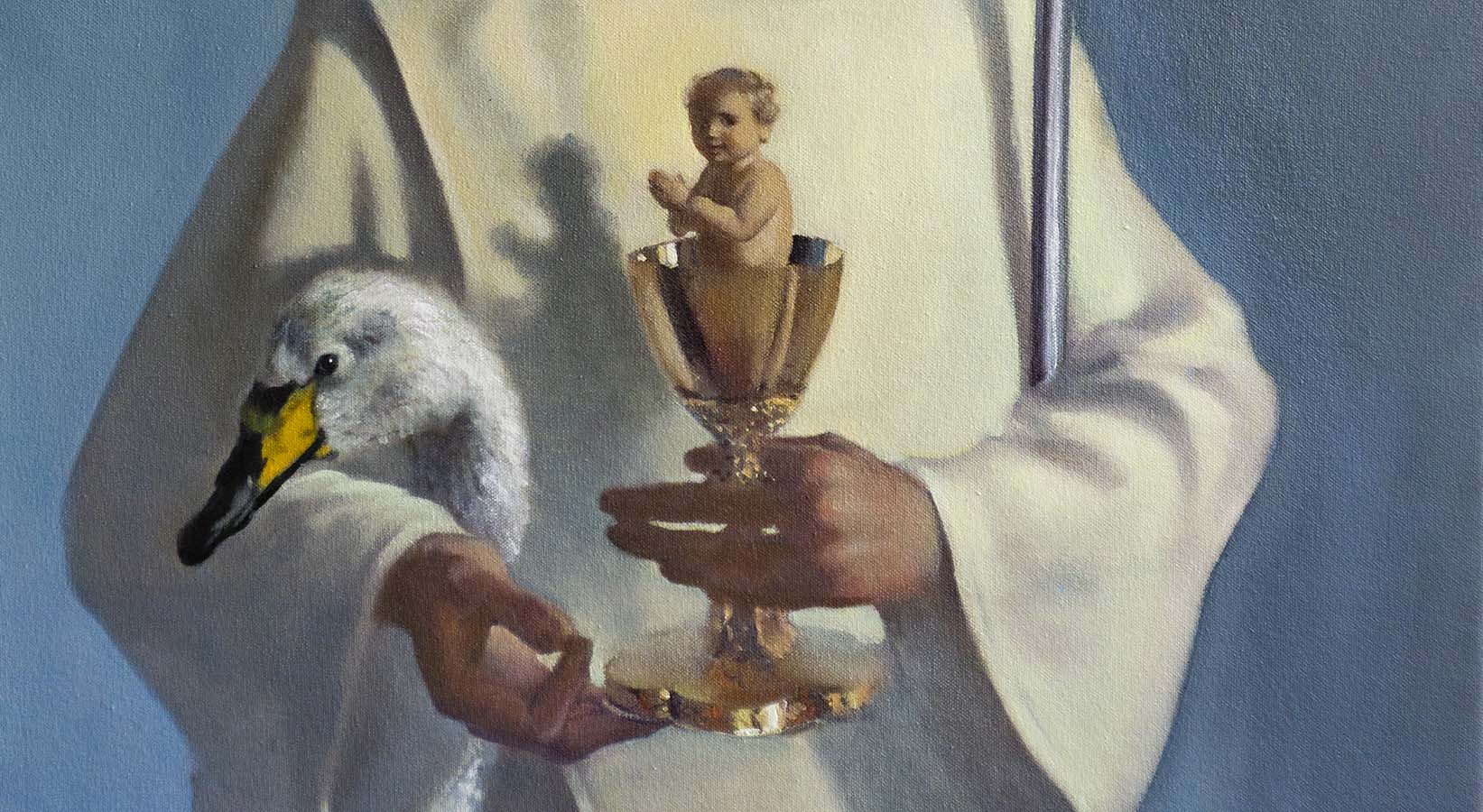

The Chalice and the Christ Child

If Gwyneth achieved her effect, after the initial impression of a Carthusian monk standing in warm light in an austere monastery, the viewer of St. Hugh of Lincoln should be captivated first by the chalice and the Christ Child emerging from it. The emblem alludes to one of several Eucharistic miracles involving the saint, when a young cleric was sent by God to ask St. Hugh “to urgently draw the attention of the Archbishop of Canterbury to the state of the clergy in England. Reform is grievously needed, and the Divine Majesty is deeply offended by innumerable abuses.”

God had assured the young man that his credibility would be established by telling St. Hugh what he was to see at Hugh’s pontifical Mass. At the consecration of the Mass, the man saw “a little child, very small but of Divine and entrancing beauty, resting in the Bishop’s hands.” Immediately after Mass, the cleric approached St. Hugh and told him what he had seen: “the Body of our Lord Jesus Christ, under the form of a little Child, whom you twice raised above the chalice.” St. Hugh redoubled his own efforts at clerical reform in the Diocese of Lincoln, but was unable to convince the Archbishop of Canterbury to attend to the reform of the whole Church in England. (Life of St. Hugh, pages 340-345 and 357.)

“The story is extremely timely,” Gwyneth notes. “I think it offers a pattern of true reform: reform rooted in the centrality of the Eucharist.”

Gwyneth’s treatment of the chalice was especially inspired by consulting Baroque depictions of armor, including some paintings at the St. Louis Art Museum. “When St. Paul tells us to put on the armor of God,” she says, “I see an allusion now to the chalice; perhaps others will too.”

In person, the chalice has a subtle sculptural quality distinct from the rest of the painting. She achieved this through the use of impasto—thick globs of paint—in the lights, a technique exploited beautifully by Rembrandt and Frans Hals in the 17th century. Using impasto is always risky, says Gwyneth. “You can’t fiddle with it or you lose the vitality; it becomes mere globs of paint rather than bringing something else to life. It has taken me a long time to feel confident enough to employ impasto.” Painting the chalice became Gwyneth’s favorite part of this painting.

St. Hugh holds the chalice with large, Mannerist hands, his thumbs and forefingers touching according to the ancient position of the priest’s fingers from the Consecration to the Ablutions.

Gwyneth elected to direct the Christ Child’s eyes outward toward the viewer, in distinction to Hugh’s own eyes, which are averted. “Hugh is not thinking of himself, of course, but of God,” Gwyneth explains. “But I wanted the Christ Child to address the viewer, drawing him into the contemplation of St. Hugh.”

St. Hugh in the Heavenly Chartreuse

Gwyneth’s St. Hugh of Lincoln is an invitation to contemplate the great saint anew in order to follow him in conforming our lives to Christ. From the initial impression of a Carthusian monk standing in a sunlit monastery down to the shining gold detailing of the chalice, the painting challenges us and our age to reevaluate our priorities in the light of St. Hugh’s.

The perspicuity of St. Hugh’s vision of what matters is also visible in his face. “He has a sense of calm seriousness, but also a sense of humor,” says Gwyneth. “Although he is not smiling, it is a face that could smile, that does smile.”

Yet it is important to Gwyneth that St. Hugh is not smiling. “Today we are accustomed to seeing our relatives and even our prelates grinning at us from portraits. In the past this was never so,” she notes. The smile is necessarily a momentary gesture, something fugitive. It becomes uncanny when captured in perpetuity. The saint lives always in contemplation of eternal things. The gravity and profundity of his vision, Gwyneth argues, ought to be on display in all his depictions.

Stylistically, too, Gwyneth sought to convey a supernatural vision. She describes the painting’s style as a “simplified naturalism.” Every element is taken from the observation of nature, but every form is simplified. The idea is that the viewer should not get lost in the curiositas of postlapsarian vision that analyzes things independently of God; instead he should have his vision renewed, seeing all things in the light of God through the holy vision of St. Hugh.

The saint is cast in a warm afternoon light that gently gilds his white habit. “It’s a transfigured vision, the sight of a visionary,” says Gwyneth. The light was inspired by the light in Perugino’s Vision of St. Bernard in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich. Gwyneth’s St. Hugh of Lincoln is indeed the portrait of a Carthusian monk standing steady at the foot of the Cross while the world turns, but a Carthusian monk translated into the heavenly Chartreuse.

Browse preparatory drawings for St. Hugh of Lincoln in the Shop.